Hollywood producer Boris Morros was famous for his wild antics, but even he might not have believed the outrageous scheme he was about to hatch in this flamingo-pink booth. Across from him sat Vasily Zarubin, the NKGB’s top spy in America. The Soviet intelligence officer peered over the table at Boris, glass of vodka in hand. “What about taking my men into your music company?” he said.

Under the clatter of plates and chirpy conversations at nearby tables, Boris considered the offer. For this clandestine lunch in February of 1943, Zarubin had chosen the showiest restaurant on Wilshire Boulevard. Perino’s was famous for its crab legs and pink décor, but its outstanding attraction were the plush, high-backed booths that advertised their glamorous occupants. Hollywood gossip columnists dined at Perino’s for a chance at a scoop. Bette Davis had her own booth. So did mobster Bugsy Siegel. It was a curious location, then, to hatch a Soviet espionage scheme. Then again, even communist spies liked to hobnob.

Boris weighed his choices. With its headquarters at Sunset and Vine, the Boris Morros Music Company was only a modest sheet-music publishing house, but its ambitious owner had bigger dreams for it. Those didn’t include putting Soviet spies on the payroll. His ambitions did require a sizable investment, however, and here Boris, who had survived — at moments even thrived — during his two decades in the entertainment industry, smelled opportunity.

Yes, Boris replied at last. If Moscow helped him expand the business, he could easily justify a few talent scouts and performance rights agents.

“Sounds like a perfect cover,” Zarubin, a heavy drinker, purred. “We could have men around the United States and a few in South America — all on your payroll.” Lost in the brilliance of his scheme, the Soviet spymaster continued, “It would seem natural for a music company to have men working in other countries, finding native songs and developing talent, making tie-ups with foreign music publishers. They’d have every excuse in the world to keep moving about.” There was just the question of money. Boris, a former Paramount Pictures executive who’d carved out a tenuous foothold as an independent producer and music publisher, would need a substantial investment, he insisted, to support the espionage work.

Zarubin noodled this over, acutely aware how difficult it would be to extract hard currency from Moscow. He proposed a more creative funding source. Imperial Russia’s art collections had fallen into the hands of the Bolsheviks. Perhaps a few masterpieces could make their way to Boris’ house in Beverly Hills, he offered, where Boris would sell the Raphaels and Rembrandts and invest the proceeds in the music company.

Boris dismissed that as preposterous. He was no art dealer. Zarubin would have to come up with cash.

A few months later, Zarubin summoned Boris back to Perino’s. “I’ve decided,” he announced after a few glasses of vodka, “that we’ll expand your music company,” adding that financing would be no problem. He’d found an investor, a wealthy American whose new wife, a true believer in the Marxist-Leninist ideal, had turned her husband into a Soviet asset. They would back the mission by becoming business partners with Boris. Slipping toward drunkenness in the high-backed booth, Zarubin seemed exuberant.

Boris, excited at the prospect of investment in his fledgling business and curious about his new business partners, was suddenly rattled by a serious-looking young man in a neighboring booth who seemed out of place among the Hollywood glitz and glam. When the man made eye contact with Boris, even going so far as to wink, the stunned producer, a legendary schmoozer who usually solicited attention, went cold.

Was this man eavesdropping, he wondered, as he hoisted his glass to seal the new business arrangement? And for whom?

Before the year’s end, Boris was sitting in the passenger seat of a NKGB sedan as Zarubin, his nervous eyes scanning the rear-view mirror, drove deep into the snow-flocked Connecticut countryside. Soon they arrived at a sprawling country estate outside the town of Ridgefield, where Boris was to meet his new investors.

Although no true believer himself, Boris had few qualms about helping the Soviets. He was an opportunist, a hustler in the best tradition of Hollywood, and he had identified an upside to this arrangement.

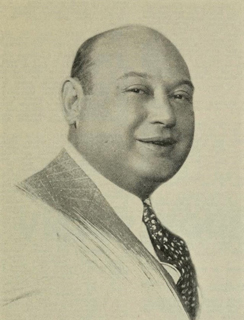

Boris Morros

Bald and roly-poly fat, the 52-year-old producer had emigrated from Russia to America in 1922 and still carried an accent, which he used to uproarious effect. He liked to repeat the old show-business adage, “A little embellishment never ruined a good story,” and Boris was full of stories. Born to humble Jewish parents, he boasted that he once played fiddle for the czar and sipped tea with Tchaikovsky, who died when Boris was two years old. At meetings in his office, he twirled a string of amber beads and insisted that Rasputin, impressed with his witty banter, had given him the rosary. Boris didn’t talk, he gushed, clutching his listener’s hand until his story found its punch line. His innate charm helped him climb the ranks at Paramount, where he became general music director in 1935 and turned the film score into an art form, collecting three Oscar nominations. More recently, he’d struck out as an independent producer, the man behind the fifth-highest grossing film of 1942, Tales of Manhattan.

In a town that collected colorful personalities, Boris stood out. At studio Christmas parties he walked around with two seemingly identical bottles of vodka and insisted that everyone drink with him. While colleagues grew inebriated swigging 80-proof, he gulped from a bottle filled with water. But even his most outrageous hijinks paled next to his sartorial choices: He wore the wildest combinations of ties and shirts, stripes on plaid, clashing colors. “How else,” he once explained, “would anybody ever notice me in this big place?”

In an odd way, his cartoonish persona helped mask suspicion that his Russian origins might otherwise have garnered, putting people at ease even as anti-communist paranoia began to grip Hollywood. McCarthy’s witch hunt and the Hollywood blacklist loomed just a few years out, but Boris seemed too obvious to be any kind of threat.

The Soviets didn’t think so, however. Boris’ career in espionage began in 1933 when a talent agent offered him the exiled communist Leon Trotsky, by then out of favor with the Soviet authorities, as a performer. Boris, who at the time was supervising live stage shows for Paramount’s theater chain, just couldn’t picture a future in show business for an exiled Bolshevik fulminating on stage against Stalin, and so he gave Trotsky’s agent a show-business “no”: He said he’d think about it.

Almost immediately, his secretary began receiving phone calls from a man with a Russian accent who identified himself as a Soviet trade representative and claimed he had business to discuss. What a pity, the trade representative said over lunch at the Hotel Astor, that Boris’ brothers, still in Russia, were on such bad terms with the Soviet government.

This was news to Boris. To his knowledge, they were loyal Party members.

As quickly as the mysterious Russian had raised Boris’ alarm, he tried to put him at ease. “We can be very useful to each other, my friend.” Stalin was determined to keep Trotsky, his arch-nemesis off the stage. “I understand you want to book Trotsky. Don’t book.”

“All right,” Boris said, neglecting to mention he had independently reached that conclusion. “If you don’t want Trotsky booked into the Paramount, I can promise you he will never appear there as long as I am in charge of the stage shows.”

In return, the mysterious Russian not only pledged to help Boris’ family, he also secured permission for Boris’ father to bypass the Soviet Union’s notorious migration controls and visit America. As father and son walked the streets of Manhattan together and vacationed in Florida, Boris — now a Soviet agent with the codename FROST — realized how much influence he could wield through the simple exchange of favors with the world’s most feared intelligence service. He also realized the various benefits the relationship could afford as his own bright star was rising as a Hollywood operator. Boris would exploit his relationship with Soviet intelligence for his own gain. It was a lucrative, thrilling, and, yes, dangerous, side-hustle.

Now he was about to begin its next chapter. Climbing out of the car, Boris and Zarubin crunched across the snow toward a massive New England farmhouse.

A small, pretty woman in her mid-30s emerged to meet them. She shook hands with Boris, who then watched as the woman wrapped her arms around “Vasya” Zarubin, as she affectionately called him, and kissed him on the lips. They held the embrace like it was the closing shot of a romantic movie. Embarrassment crept across Boris’ face until, finally, a meek voice protested: “Now, Vasya, that’s enough.” It was the woman’s husband.

Martha Dodd and Alfred K. Stern were a study in contrasts. Martha was vivacious and sensual; Alfred was quiet and demure. She chased adventure; he sought safety. Nevertheless, they found common cause in their concern for social justice, their affinity for international communism, and their eagerness to do Moscow’s bidding.

Martha was attractive, even gravitational, in a way her physical description — thirty-five and petite, wavy blonde hair and a subtle yet distinctive overbite — could never capture. When her father was appointed U.S. ambassador to Nazi Germany in 1933, she moved with him to Berlin and found herself overwhelmed with attention. Love letters from Carl Sandburg and Thomas Wolfe, both old family friends, piled up. At one point, as she found herself briefly enchanted by the goose-stepping storm troopers and flowing red banners, a Nazi matchmaker set her up with Adolf Hitler. At the appointed rendezvous at the Kaiserhof Hotel, the Führer kissed her on the hand, twice — but that was as far as it got. Hitler, she later concluded, was “a frigid celibate.”

Martha Dodd

When Hitler couldn’t satisfy her, Martha soon found true love with a tall, handsome English-speaking press attaché from the Soviet embassy. The couple escaped to Paris, then Moscow, and only later did she learn that her paramour was an NKVD officer with orders to recruit her into the service. Nevertheless, Martha joined willingly, dished State Department secrets to Moscow, and remained loyal to the Sovet Union — even after her lover fell victim to one of Stalin’s purges.

Upon returning to the U.S., Martha became an NKGB talent spotter. Her methods were quirky — she once submitted a report on 53 potential contacts in the form of a screenplay — but she got results. Among Martha’s most significant recruits was an espionage power couple, the wife an operative with the top-secret Office of Strategic Services, the husband a counterintelligence officer for the U.S. Army.

But her most improbable recruit, a millionaire communist, gave her the most pride — not least because the Red millionaire happened to be her own husband, whom Martha, a friend later wrote, “ruled with an iron hand wrapped in a thick velvet glove.” Eleven years her senior, Alfred K. Stern was a thin, lanky man with a pockmarked face and toothbrush mustache. More to the point, Stern was the divorcé of a Sears, Roebuck heiress, and he was eager to spend his fortune for the Cause.

“Now we have no more trouble about money,” said Zarubin, in a cheery mood. “Here is our treasury, our millionaire. All you have to do is set him up in the business and train him as a music company executive.”

It wasn’t actually that simple — negotiations stretched on for several days in the Sterns’ library — but eventually they reached a deal. The Sterns would invest $130,000 into the Boris Morros Music Company, in return for a twenty-five percent annual dividend and Alfred’s appointment as vice president.

Lawyers drew up a contract. On New Year’s Eve 1943, Alfred Stern arrived at Boris’ Manhattan hotel room to sign. Zarubin, who came along as a witness, was in a jubilant mood, declaring that Operation CHORD was to be the “crown in his work,” providing cover to a generation of “illegals,” as Soviet intelligence officers with non-official cover were known. Downing a few swigs of vodka, he broke out into a Red Army song, “If Tomorrow Brings War,” but stopped mid-verse when he saw Stern pick up the contract. “Don’t read it, you stupid son of a bitch! Just sign it.”

Stern sighed. He took out his fountain pen and scribbled his name.

As Boris returned to Los Angeles with his corporate coffers overflowing, his original business plan suddenly seemed too modest. The Sterns’ investment valued the Boris Morros Music Company at north of a half million dollars — this for a firm he’d started with no more than six grand! With that kind of capital, he could do more than issue sheet music. He could take on Columbia, Decca, RCA Victor. He could build a record label.

And so, even as his company started printing sheet music, Boris began funneling the Sterns’ money into his new idea. He rented a factory at 686 North Robertson in West Hollywood, purchased four record presses, and signed top acts to recording contracts.

Before long, a full-page advertisement appeared on the inside front cover of Billboard. “Proudly we announce a new name in phonograph records,” it boasted, “an outstanding achievement in recorded music with the presentation of these famous artists!” Those artists’ faces smiled up from the Billboard ad: Hoagy Carmichael, Frances Langford, Bob Crosby, brother of Bing.

American Recording Artists, or ARA Records, was born.

When the Sterns questioned this unexpected development, Boris informed them, matter-of-factly, that the economics of the music business had changed. A publishing house couldn’t survive without a record company to popularize its tunes. “It’s a simple formula,” he explained. “With a record, you only have to listen, but for sheet music, you have to know how to play.” Though they remained skeptical, the Sterns accepted his decision.

Even as Boris wooed emerging talent to his label — Phil Harris, Skinny Ennis, Rosa Linda, the Town Criers — he sought out innovative projects that would distinguish ARA from the competition. He struck a deal with the Catholic Church, for example, to issue a quadruple-album by the famed Vatican Sistine Chapel Chorus. And, through a partnership with producer David O. Selznick, ARA pioneered the use of a soundtrack album to promote a film, with Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound. The score went on to win an Oscar.

By March 1945, ARA records were getting regular radio airplay. Sales of their first hit, Joe Reichman’s western single “There’s Nobody Home on the Range,” were strong. American Recording Artists, it seemed, was well on its way to becoming another Capitol Records, a permanent West Coast fixture in the record industry.

It was not, however, living up to its billing as a top notch spy operation, and for Agent FROST’s increasingly suspicious business partners, that was a problem.

If anyone could see through Boris Morros, it was Martha Dodd Stern.

The ambassador’s daughter got her first lesson in tradecraft from one of her early lovers back in Germany, a man she recalled as “a human monster of sensitive face and cruel, broken beauty.” Over the course of their unlikely romance, Rudolf Diels, head of Nazi Germany’s Gestapo, or secret police, introduced a naive Martha to a hidden world of intrigue. Once, the secret police chief even showed Martha his office, where she noticed a variety of listening devices strewn about his desk.

“There began to appear before my romantic eyes,” she remembered, “a vast and complicated network of espionage, terror, sadism and hate, from which no one, official or private, could escape.” Nazi Germany was descending into paranoia and simmering with violence. By the end of the affair, Dodd was covering the telephone with a pillow and questioning every moving shadow she saw, every footstep she heard, a preternatural suspicion she would carry for the rest of her life.

If Boris shared anything with Martha, it was the thrill of maneuvering through a secret world and a familiarity with the dangers of life under a murderous regime. His life — half of it played out in front of the bright lights of Hollywood, the other half in the shadows — had become something of a fantasy, as if he were starring in one of his own movies. And his ambitions grew with his success. Boris had his eyes on a promising new technology with the potential to revolutionize Hollywood — pictures beamed directly into American living rooms. If the NKGB could capitalize his record label, perhaps it could provide the funding for a television company, too.

Why not? Boris was lining his open pockets and raising his own profile at Moscow’s expense, and if he was quickly becoming a Hollywood mogul, no one in the Soviet intelligence service seemed to care.

No one, that is, except his new business partner’s wife.

Martha had grown wary as American Recording Artists released travesties like “There’s Nobody Home on the Range” but still couldn’t manage to put a single undercover spy on the payroll. So far, Boris had offered only two small concessions to his music company’s true, clandestine purpose. His record deal with the Sistine Chapel choir, he insisted, was merely the groundwork for opening a branch office in Rome. He also tried to reassure the Sterns by sending a company rep named Stone to Mexico, even referring to him as “our man in Mexico City.” But “our man,” it turned out, was no spy. He was a bona fide composer from Los Angeles, and he had no knowledge of the company’s secret intentions.

The Sterns brought their concerns to Zarubin, who didn’t want to hear them. He announced that he’d been promoted to major general and was handing over Operation CHORD to one of his subordinates, a Lithuanian intelligence officer named Jack Soble. But before doing so he wanted to make one thing clear. “Our Comrade here,” he said of Boris, “is completely devoted to the motherland, and is one of our most trusted and loyal agents.”

That display of confidence couldn’t stop the business partners from growing apart. The geographic distance between them didn’t help. Martha hated Hollywood, so Alfred Stern, vice president, worked out of his seventeenth-floor office at 30 Rockefeller Plaza while Boris headed up affairs in California. Alfred got into the habit of mailing daily letters, each several pages long, questioning Boris’ every move. He wanted to fire Boris’ talented sales manager, Shelby Yorke, and criticized Boris’ talent signings, once asking “Why don’t we sign Bing Crosby instead of his brother Bob?” (Bing was already under contract at Decca.)