Chapter 13

THE FOURTH PLANET belonged to a businessman. This person was so busy that he didn’t even raise his head when the little prince arrived.

“Hello,” said the little prince. “Your cigarette’s gone out.”

“Three and two make five. Five and seven, twelve. Twelve and three, fifteen. Hello. Fifteen and seven, twenty-two. Twenty-two and six, twenty-eight. No time to light it again. Twenty-six and five, thirty-one. Whew! That amounts to five-hundred-and-one million, six hundred-twenty-two thousand, seven hundred thirty-one.”

“Five-hundred million what?”

“Hmm? You’re still there? Five-hundred-and-one million… I don’t remember… I have so much work to do! I’m a serious man. I can’t be bothered with trifles! Two and five, seven…”

“Five-hundred-and-one million what?” repeated the little prince, who had never in his life let go of a question once he had asked it.

The businessman raised his head.

“For the fifty-four years I’ve inhabited this planet, I’ve been interrupted only three times. The first time was twenty-two years ago, when I was interrupted by a beetle that had fallen onto my desk from god knows where. It made a terrible noise, and I made four mistakes in my calculations. The second time was eleven years ago, when I was interrupted by a fit of rheumatism. I don’t get enough exercise. I haven’t time to take strolls. I’m a serious person. The third time… is right now! Where was I? Five hundred-and-one million…”

“Million what?”

The businessman realized that he had no hope of being left in peace.

“Oh, of those little things you sometimes see in the sky.”

“Flies?”

“No, those little shiny things.”

“Bees?”

“No, those little golden things that make lazy people daydream. Now, I’m a serious person. I have no time for daydreaming.”

“Ah! You mean the stars?”

“Yes, that’s it. Stars.”

“And what do you do with five-hundred million stars?”

“Five-hundred-and-one million, six-hundred- twenty-two thousand, seven hundred thirty-one. I’m a serious person, and I’m accurate.”

“And what do you do with those stars?”

“What do I do with them?”

“Yes.”

“Nothing. I own them.”

“You own the stars?”

“Yes.”

“But I’ve already seen a king who -”

“Kings don’t own. They ‘reign’ over… It’s quite different.”

“And what good does owning the stars do you?”

“It does me the good of being rich.”

“And what good does it do you to be rich?”

“It lets me buy other stars, if somebody discovers them.”

The little prince said to himself, “This man argues a little like my drunkard.” Nevertheless he asked more questions. “How can someone own the stars?”

“To whom do they belong?” retorted the businessman grumpily.

“I don’t know. To nobody.”

“Then they belong to me, because I thought of it first.”

“And that’s all it takes?”

“Of course. When you find a diamond that belongs to nobody in particular, then it’s yours. When you find an island that belongs to nobody in particular, it’s yours. When you’re the first person to have an idea, you patent it and it’s yours. Now I own the stars, since no one before me ever thought of owning them.”

“That’s true enough,” the little prince said. “And what do you do with them?”

“I manage them. I count them and then count them again,” the businessman said. “It’s difficult work. But I’m a serious person!”

The little prince was still not satisfied. “If I own a scarf, I can tie it around my neck and take it away. If I own a flower, I can pick it and take it away. But you can’t pick the stars!”

“No, but I can put them in the bank.”

“What does that mean?”

“That means that I write the number of my stars on a slip of paper. And then I lock that slip of paper in a drawer.”

“And that’s all?”

“That’s enough!”

“That’s amusing,” thought the little prince. “And even poetic. But not very serious.” The little prince had very different ideas about serious things from those of the grown-ups. “I own a flower myself,” he continued, “which I water every day. I own three volcanoes, which I rake out every week. I even rake out the extinct one. You never know. So it’s of some use to my volcanoes, and it’s useful to my flower, that I own them. But you’re not useful to the stars.”

The businessman opened his mouth but found nothing to say in reply, and the little prince went on his way.

“Grown-ups are certainly quite extraordinary,” was all he said to himself as he continued on his journey.

Chapter 14

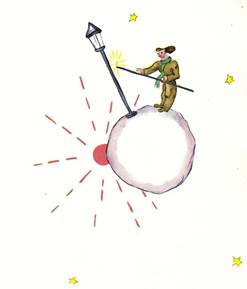

THE FIFTH PLANET was very strange. It was the smallest of all. There was just enough room for a street lamp and a lamplighter. The little prince couldn’t quite understand what use a street lamp and a lamplighter could be up there in the sky, on a planet without any people and not a single house. However, he said to himself:

" It’s quite possible that this man is absurd. But he’s less absurd than the king, the very vain man, the business-man, and the drunkard. At least his work has some mean-ing. When he lights his lamp, it’s as if he’s bringing one more star to life, or one more flower. When he puts out his lamp, that sends the flower or the star to sleep. Which is a fine occupation. And therefore truly useful.”

When the little prince reached this planet, he greeted the lamplighter respectfully.

“Good morning. Why have you just put out your lamp?”

“Orders,” the lamplighter answered. “Good morning.”

“What orders are those?”

“To put out my street lamp. Good evening.”

And he lit his lamp again.

“But why have you just lit your lamp again?”

“Orders.”

“I don’t understand,” said the little prince.

“There’s nothing to understand,” said the lamplighter. “Orders are orders. Good morning.” And he put out his lamp. Then he wiped his forehead with a red-checked handkerchief.

“It’s a terrible job I have. It used to be reasonable enough. I put the lamp out mornings and lit it after dark. I had the rest of the day for my own affairs, and the rest of the night for sleeping.”

“And since then orders have changed?”

“Orders haven’t changed,” the lamplighter said. “That’s just the trouble! Year by year the planet is turning faster and faster, and orders haven’t changed!”

“Which means?”

“Which means that now that the planet revolves once a minute, I don’t have an instant’s rest. I light my lamp and turn it out once every minute!”

“That’s funny! Your days here are one minute long!”

“It’s not funny at all,” the lamplighter said. “You and I have already been talking to each other for a month.”

“A month?”

“Yes. Thirty minutes. Thirty days! Good evening.” And he lit his lamp.

The little prince watched him, growing fonder and fonder of this lamplighter who was so faithful to orders. He remembered certain sunsets that he himself used to follow in other days, merely by shifting his chair. He wanted to help his friend.

“You know… I can show you a way to take a rest whenever you want to.”

“I always want to rest,” the lamplighter said, for it is possible to be faithful and lazy at the same time.

The little prince continued, “Your planet is so small that you can walk around it in three strides. All you have to do is walk more slowly, and you’ll always be in the sun. When you want to take a rest just walk… and the day will last as long as you want it to.”

“What good does that do me?” the lamplighter said, “when the one thing in life I want to do is sleep?”

“Then you’re out of luck,” said the little prince.

“I am,” said the lamplighter. “Good morning.” And he put out his lamp.

“Now that man,” the little prince said to himself as he continued on his journey, “that man would be despised by all the others, by the king, by the very vain man, by the drunkard, by the businessman. Yet he’s the only one who doesn’t strike me as ridiculous. Perhaps it’s because he’s thinking of something beside himself.” He heaved a sigh of regret and said to himself, again, “That man is the only one I might have made my friend. But his planet is really too small. There’s not room for two…”

What the little prince dared not admit was that he most regretted leaving that planet because it was blessed with one thousand, four hundred forty sunsets every twenty-four hours!

Chapter 15

THE SIXTH PLANET was ten times bigger than the last. It was inhabited by an old gentleman who wrote enormous books.

“Ah, here comes an explorer,” he exclaimed when he caught sight of the little prince, who was feeling a little winded and sat down on, the desk. He had already traveled so much and so far!

“Where do you come from?” the old gentleman asked him.

“What’s that big book?” asked the little prince. “What do you do with it?”

“I’m a geographer,” the old gentleman answered.

“And what’s a geographer?”

“A scholar who knows where the seas are, and the rivers, the cities, the mountains, and the deserts.”

“That is very interesting,” the little prince said. “Here at last is someone who has a real profession!” And he gazed around him at the geographer’s planet. He had never seen a planet so majestic. “Your planet is very beautiful,” he said. “Does it have any oceans?”

“I couldn’t say,” said the geographer.

“Oh,” the little prince was disappointed. “And mountains?”

“I couldn’t say,” said the geographer.

“And cities and rivers and deserts?”

“I couldn’t tell you that, either,” the geographer said.

“But you’re a geographer!”

“That’s right,” said the geographer, “but I’m not an explorer. There’s not one explorer on my planet. A geographer doesn’t go out to describe cities, rivers, mountains, seas, oceans, and deserts. A geographer is too important to go wandering about. He never leaves his study. But he receives the explorers there. He questions them, and he writes down what they remember. And if the memories of one of the explorers seem interesting to him, then the geographer conducts an inquiry into that explorer’s moral character.”

“Why is that?”

“Because an explorer who told lies would cause disasters in the geography books. As would an explorer who drank too much.”

“Why is that?” the little prince asked again. “Because drunkards see double. And the geographer would write down two mountains where there was only one.”

“I know someone,” said the little prince, “who would be a bad explorer.”

“Possibly. Well, when the explorer’s moral character seems to be a good one, an investigation is made into his discovery.”

“By going to see it?”

“No, that would be too complicated. But the explorer is required to furnish proofs. For instance, if he claims to have discovered a large mountain, he is required to bring back large stones from it.” The geographer suddenly grew excited. “But you come from far away! You’re an explorer! You must describe your planet for me!”

And the geographer, having opened his logbook, sharpened his pencil. Explorers’ reports are first recorded in pencil; ink is used only after proofs have been furnished.

“Well?” said the geographer expectantly.

“Oh, where I live,” said the little prince, “is not very interesting. It’s so small. I have three volcanoes, two active and one extinct. But you never know.”

“You never know,” said the geographer.

“1 also have a flower.”

“We don’t record flowers,” the geographer said.

“Why not? It’s the prettiest thing!”

“Because flowers are ephemeral.”

“What does ephemeral mean?”

“Geographies,” said the geographer, “are the finest books of all. They never go out of fashion. It is extremely rare for a mountain to change position. It is extremely rare for an ocean to be drained of its water. We write eternal things.”

“But extinct volcanoes can come back to life,” the little prince interrupted. “What does ephemeral mean?”

“Whether volcanoes are extinct or active comes down to the same thing for us,” said the geographer. “For us what counts is the mountain. That doesn’t change.”

“But what does ephemeral mean?” repeated the little prince, who had never in all his life let go of a question once he had asked it.

”It means, ‘which is threatened by imminent disappearance.'”

“Is my flower threatened by imminent disappearance?”

“Of course.”

“My flower is ephemeral,” the little prince said to himself, “and she has only four thorns, with which to defend herself against the world! And I’ve left her all alone where I live!”

That was his first impulse of regret. But he plucked up his courage again. “Where would you advise me to visit?” he asked.

“The planet Earth,” the geographer answered. “It has a good reputation.”

And the little prince went on his way, thinking about his flower.

Chapter 16

THE SEVENTH PLANET, then, was the Earth.

The Earth is not just another planet! It contains one hundred and eleven kings (including, of course, the African kings), seven thousand geographers, nine hundred thousand businessmen, seven-and-a-half million drunkards, three-hundred-eleven million vain men; in other words, about two billion grown-ups.

To give you a notion of the Earth’s dimensions, I can tell you that before the invention of electricity, it was necessary to maintain, over the whole of six continents, a veritable army of four-hundred-sixty-two thousand, five hundred and eleven lamplighters.

Seen from some distance, this made a splendid effect. The movements of this army were ordered like those of a ballet. First came the turn of the lamplighters of New Zealand and Australia; then these, having lit their street lamps, would go home to sleep. Next it would be the turn of the lamplighters of China and Siberia to perform their steps in the lamplighters’ ballet, and then they too would vanish into the wings. Then came the turn of the lamplighters of Russia and India. Then those of Africa and Europe. Then those of South America, and of North America. And they never missed their cues for their appearances onstage. It was awe inspiring.

Only the lamplighter of the single street lamp at the North Pole and his colleague of the single street lamp at the South Pole led carefree, idle lives: They worked twice a year.

Chapter 17

TRYING TO BE WITTY leads to lying, more or less. What I just told you about the lamplighters isn’t completely true, and I risk giving a false idea of our planet to those who don’t know it. Men occupy very little space on Earth. If the two billion inhabitants of the globe were to stand close together, as they might for some big public event, they would easily fit into a city block that was twenty miles long and twenty miles wide. You could crowd all humanity onto the smallest Pacific islet.

Grown-ups, of course, won’t believe you. They’re convinced they take up much more room. They consider themselves as important as the baobabs.

So you should advise them to make their own calculations – they love numbers, and they’ll enjoy it. But don’t waste your time on this extra task. It’s unnecessary. Trust me.

So once he reached Earth, the little prince was quite surprised not to see anyone. He was beginning to fear he had come to the wrong planet, when a moon-colored loop uncoiled on the sand.

“Good evening,” the little prince Said, just in case.

“Good evening,” said the snake.

“What planet have I landed on?” asked the little prince.

“On the planet Earth, in Africa,” the snake replied.

“Ah!… And are there no people on Earth?”

“It’s the desert here. There are no people in the desert. Earth is very big,” said the snake.

The little prince sat down on a rock and looked up into the sky.

“I wonder,” he said, “if the stars are lit up so that each of us can find his own, someday. Look at my planet – it’s just overhead. But so far away!”

“It’s lovely,” the snake said. “What have you come to Earth for?”

“I’m having difficulties with a flower,” the little prince said.

“Ah!” said the snake.

And they were both silent.

“Where are the people?” The little prince finally resumed the conversation. “It’s a little lonely in the desert…”

“It’s also lonely with people,” said the snake.

The little prince looked at the snake for a long time. “You’re a funny creature,” he said at last, “no thicker than a finger.”

“But I’m more powerful than a king’s finger,” the snake said.

The little prince smiled.

“You’re not very powerful…” You don’t even have feet. You couldn’t travel very far.”

“I can take you further than a ship,” the snake said. He coiled around the little prince’s ankle, like a golden bracelet.

“Anyone I touch, I send back to the land from which he came,” the snake went on. “But you’re innocent, and you come from a star…”

The little prince made no reply.

“I feel sorry for you, being so weak on this granite earth,” said the snake. “I can help you, someday, if you grow too homesick for your planet. I can-”

“Oh, I understand just what you mean,” said the little prince, “but why do you always speak in riddles?”

“I solve them all,” said the snake.

And they were both silent.

HTML layout and style by Stephen Thomas, University of Adelaide.

Modified by Skip for ESL Bits English Language Learning.