Chapter 1

ONCE WHEN I was six I saw a magnificent picture in a book about the jungle, called True Stories. It showed a boa constrictor swallowing a wild beast. Here is a copy of the picture.

In the book it said: “Boa constrictors swallow their prey whole, without chewing. Afterward they are no longer able to move, and they sleep during the six months of their digestion.”

In those days I thought a lot about jungle adventures, and eventually managed to make my first drawing, using a colored pencil. My drawing Number One looked like this:

I showed the grown-ups my masterpiece, and I asked them if my drawing scared them.

They answered, “Why be scared of a hat?”

My drawing was not a picture of a hat. It was a picture of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. Then I drew the inside of the boa constrictor, so the grown-ups could understand. They always need explanations.

My drawing Number Two looked like this:

The grown-ups advised me to put away my drawings of boa constrictors, outside or inside, and apply myself instead to geography, history, arithmetic, and grammar. That is why I abandoned, at the age of six, a magnificent career as an artist.

I had been discouraged by the failure of my drawing Number One and of my drawing Number Two.

Grown-ups never understand anything by themselves, and it is exhausting for children to have to provide explanations over and over again.

So then I had to choose another career, and I learned to pilot airplanes. I have flown almost everywhere in the world. And, as a matter of fact, geography has been a big help to me. I could tell China from Arizona at first glance, which is very useful if you get lost during the night.

So I have had, in the course of my life, lots of encounters with lots of serious people. I have spent lots of time with grown-ups. I have seen them at close range . . . which hasn’t much improved my opinion of them.

Whenever I encountered a grown-up who seemed to me at all enlightened, I would experiment on him with my drawing Number One, which I have always kept. I wanted to see if he really understood anything.

But he would always answer, “That’s a hat.” Then I wouldn’t talk about boa constrictors or jungles or stars. I would put myself on his level and talk about bridge and golf and politics and neckties. And my grown-up was glad to know such a reasonable person.

Chapter 2

SO I LIVED all alone, without anyone I could really talk to, until I had to make a crash landing in the Sa-hara Desert six years ago. Something in my plane’s engine had broken, and since I had neither a mechanic nor passengers in the plane with me, I was preparing to undertake the difficult repair job by myself. For me it was a matter of life or death: I had only enough drink-ing water for eight days.

The first night, then, I went to sleep on the sand a thousand miles from any inhabited country. I was more isolated than a man shipwrecked on a raft in the middle of the ocean. So you can imagine my surprise when I was awakened at daybreak by a funny little voice saying, “Please . . . draw me a sheep . . .”

“What?”

“Draw me a sheep…”

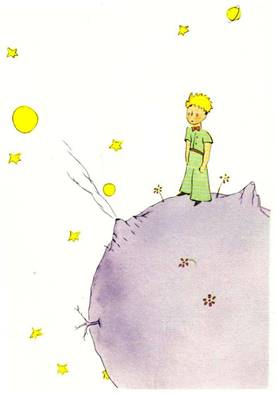

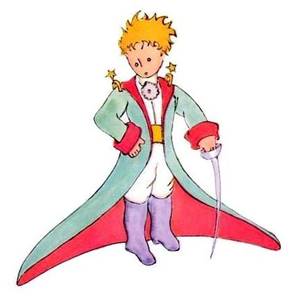

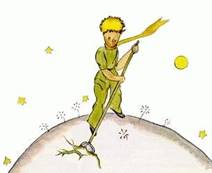

I leaped up as if I had been struck by lightning. I rubbed my eyes hard. I stared. And I saw an extraordinary little fellow staring back at me very seriously. Here is the best portrait 1 managed to make of him, later on.

But of course my drawing is much less attractive than my model.

This is not my fault. My career as a painter was discouraged at the age of six by the grown-ups, and I had never learned to draw anything except boa constrictors, outside and inside.

So I stared wide-eyed at this apparition. Don’t forget that I was a thousand miles from any inhabited territory. Yet this little fellow seemed to be neither lost nor dying of exhaustion, hunger, or thirst; nor did he seem scared to death. There was nothing in his appearance that suggested a child lost in the middle of the desert a thousand miles from any inhabited territory.

When I finally managed to speak, I asked him, “But… what are you doing here?”

And then he repeated, very slowly and very seriously, “Please… draw me a sheep…”

In the face of an overpowering mystery, you don’t dare disobey. Absurd as it seemed, a thousand miles from all inhabited regions and in danger of death, I took a scrap of paper and a pen out of my pocket. But then I remembered that I had mostly studied geography, history, arithmetic, and grammar, and I told the little fellow (rather crossly) that I didn’t know how to draw.

He replied, “That doesn’t matter. Draw me a sheep.”

Since I had never drawn a sheep, I made him one of the only two drawings I knew how to make – the one of the boa constrictor from outside. And I was astounded to hear the little fellow answer:

“No! No! I don’t want an elephant inside a boa constrictor. A boa constrictor is very dangerous, and an elephant would get in the way. Where I live, everything is very small. I need a sheep. Draw me a sheep.”

So then I made a drawing

He looked at it carefully, and then said, “No. This one is already quite sick. Make another.”

I made another drawing.

My friend gave me a kind, indulgent smile:

“You can see for yourself… that’s not a sheep, it’s a ram. It has horns…”

So I made my third drawing. But it was rejected, like the others:

“This one’s too old. I want a sheep that will live a long time.”

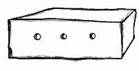

So then, impatiently, since I was in a hurry to start work on my engine, I scribbled this drawing:

And added, “This is just the crate. The sheep you want is inside.”

But I was amazed to see my young critic’s face light up.

“That’s just the kind I wanted! Do you think this sheep will need a lot of grass?”

“Why?”

“Because where I live, everything is very small…”

“There’s sure to be enough. I’ve given you a very small sheep.”

He bent over the drawing. “Not so small as all that…” Look! He’s gone to sleep…”

And that’s how I made the acquaintance of the little prince

Chapter 3

IT TOOK ME a long time to understand where he came from. The little prince, who asked me so many questions, never seemed to hear the ones I asked him.

It was things he said quite at random that, bit by bit, explained everything. For instance, when he first caught sight of my airplane (I won’t draw my airplane; that would be much too complicated for me) he asked:

“What’s that thing over there?”

“It’s not a thing. It flies. It’s an airplane. My airplane.”

And I was proud to tell him I could fly. Then he exclaimed:

“What! You fell out of the sky?”

“Yes,” I said modestly.

“Oh! That’s funny…” And the little prince broke into a lovely peal of laughter, which annoyed me a good deal. I like my misfortunes to be taken seriously. Then he added, “So you fell out of the sky, too. What planet are you from?”

That was when I had the first clue to the mystery of his presence, and I questioned him sharply.

“Do you come from another planet?”

But he made no answer. He shook his head a little, still staring at my airplane.

“Of course, that couldn’t have brought you from very far…”

And he fell into a reverie that lasted a long while. Then, taking my sheep out of his pocket, he plunged into contemplation of his treasure.

You can imagine how intrigued I was by this hint about “other planets.” I tried to learn more: “Where do you come from, little fellow? Where is this ‘where I live’ of yours? Where will you be taking my sheep?”

After a thoughtful silence he answered, “The good thing about the crate you’ve given me is that he can use it for a house after dark.”

“Of course. And if you’re good, I’ll give you a rope to tie him up during the day. And a stake to tie him to.”

This proposition seemed to shock the little prince. “Tie him up? What a funny idea!”

“But if you don’t tie him up, he’ll wander off somewhere and get lost.”

My friend burst out laughing again.

“Where could he go?”

“Anywhere. Straight ahead…”

Then the little prince remarked quite seriously, “Even if he did, everything’s so small where I live!” And he added, perhaps a little sadly, “Straight ahead, you can’t go very far.”

Chapter 4

THAT WAS HOW I had learned a second very important thing, which was that the planet he came from was hardly bigger than a house!

That couldn’t surprise me much. I knew very well that except for the huge planets like Earth, Jupiter, Mars, and Venus, which have been given names, there are hundreds of others that are sometimes so small that it’s very difficult to see them through a telescope. When an astronomer discovers one of them, he gives it a number instead of a name. For instance, he would call it “Asteroid 325.”

I have serious reasons to believe that the planet the little prince came from is Asteroid B-612.

This asteroid has been sighted only once by telescope, in 1909 by a Turkish astronomer, who had then made a formal demonstration of his discovery at an International Astronomical Congress.

But no one had believed him on account of the way he was dressed. Grown-ups are like that.

Fortunately for the reputation of Asteroid B-612, a Turkish dictator ordered his people, on pain of death, to wear European clothes. The astronomer repeated his demonstration in 1920, wearing a very elegant suit. And this time everyone believed him.

If I’ve told you these details about Asteroid B-612 and if I’ve given you its number, it is on account of the grown-ups. Grown-ups like numbers. When you tell them about a new friend, they never ask questions about what really matters. They never ask: “What does his voice sound like?”

“What games does he like best?”

“Does he collect butterflies?”

They ask: “How old is he?”

“How many brothers does he have?”

“How much does he weigh?”

“How much money does his father make?” Only then do they think they know him. If you tell grown-ups, “I saw a beautiful red brick house, with geraniums at the windows and doves on the roof…” they won’t be able to imagine such a house. You have to tell them, “I saw a house worth a hundred thousand francs.” Then they exclaim, “What a pretty house!”

So if you tell them: “The proof of the little prince’s existence is that he was delightful, that he laughed, and that he wanted a sheep. When someone wants a sheep, that proves he exists,” they shrug their shoulders and treat you like a child!

But if you tell them: “The planet he came from is Asteroid B-612,” then they’ll be convinced, and they won’t bother you with their questions. That’s the way they are. You must not hold it against them. Children should be very understanding of grown-ups.

But, of course, those of us who understand life couldn’t care less about numbers! I should have liked to begin this story like a fairytale. I should have liked to say:

“Once upon a time there was a little prince who lived on a planet hardly any bigger than he was, and who needed a friend…” For those who understand life, that would sound much truer.

The fact is, I don’t want my book to be taken lightly. Telling these memories is so painful for me. It’s already been six years since my friend went away, taking his sheep with him. If I try to describe him here, it's so I won’t forget him. It’s sad to forget a friend. Not everyone has had a friend. And I might become like the grown-ups who are no longer interested in anything but numbers. Which is still another reason why I’ve bought a box of paints and some pencils. It’s hard to go back to drawing, at my age, when you’ve never made any attempts since the one of a boa from inside and the one of a boa from outside, at the age of six!

I’ll certainly try to make my portraits as true to life as possible. But I’m not entirely sure of succeeding. One drawing works, and the next no longer bears any resemblance. And I’m a little off on his height, too. In this one the little prince is too tall. And here he's too short. And I’m uncertain about the color of his suit. So I grope in one direction and another, as best I can. In the end, I’m sure to get certain more important details all wrong. But here you’ll have to forgive me. My friend never ex-plained anything. Perhaps he thought I was like himself. But I, unfortunately, cannot see a sheep through the sides of a crate. I may be a little like the grown-ups. I must have grown old.

Chapter 5

EVERY DAY I’D LEARN something about the little prince’s planet, about his departure, about his journey. It would come quite gradually, in the course of his remarks. This was how I learned, on the third day, about the drama of the baobabs.

This time, too, I had the sheep to thank, for suddenly the little prince asked me a question, as if overcome by a grave doubt.

“Isn’t it true that sheep eat bushes?”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“Ah! I’m glad.”

I didn’t understand why it was so important that sheep should eat bushes.

But the little prince added:

“And therefore they eat baobabs, too?”

I pointed out to the little prince that baobabs are not bushes but trees as tall as churches, and that even if he took a whole herd of elephants back to his planet, that herd couldn’t finish off a single baobab.

The idea of the herd of elephants made the little prince laugh.

“We’d have to pile them on top of one another.”

But he observed perceptively:

“Before they grow big, baobabs start out by being little.”

“True enough! But why do you want your sheep to eat little baobabs?”

He answered, “Oh, come on! You know!” as if we were talking about something quite obvious. And I was forced to make a great mental effort to understand this problem all by myself.

And, in fact, on the little prince’s planet there were – as on all planets – good plants and bad plants. The good plants come from good seeds, and the bad plants from bad seeds. But the seeds are invisible.

They sleep in the secrecy of the ground until one of them decides to wake up. Then it stretches and begins to sprout, quite timidly at first, a charming, harmless little twig reaching toward the sun. If it’s a radish seed, or a rosebush seed, you can let it sprout all it likes. But if it’s the seed of a bad plant, you must pull the plant up right away, as soon as you can recognize it.

As it happens, there were terrible seeds on the little prince’s planet… baobab seeds. The planet’s soil was infested with them. Now if you attend to a baobab too late, you can never get rid of it again. It overgrows the whole planet.

Its roots pierce right through. And if the planet is too small, and if there are too many baobabs, they make it burst into pieces.

“It’s a question of discipline,” the little prince told me later on. “When you’ve finished washing and dressing each morning, you must tend your planet. You must be sure you pull up the baobabs regularly, as soon as you can tell them apart from the rosebushes, which they closely resemble when they’re very young. It’s very tedious work, but very easy.”

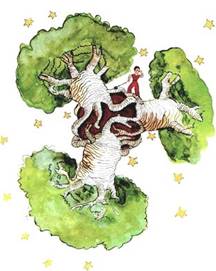

And one day he advised me to do my best to make a beautiful drawing, for the edification of the children where I live.

“If they travel someday,” he told me, “it could be useful to them. Sometimes there’s no harm in postponing your work until later. But with baobabs, it’s always a catastrophe. I knew one planet that was inhabited by a lazy man. He had neglected three bushes…”

So, following the little prince’s instructions, I have drawn that planet. I don’t much like assuming the tone of a moralist. But the danger of baobabs is so little recognized, and the risks run by anyone who might get lost on an asteroid are so considerable, that for once I am making an exception to my habitual reserve. I say, “Children, watch out for baobabs!”

It’s to warn my friends of a danger of which they, like myself, have long been unaware that I worked so hard on this drawing. The lesson I’m teaching is worth the trouble.

You may be asking, “Why are there no other drawings in this book as big as the drawing of the baobabs?” There’s a simple answer: I tried but I couldn’t manage it. When I drew the baobabs, I was inspired by a sense of urgency.

Chapter 6

O LITTLE PRINCE!

Gradually, this was how I came to understand your sad little life. For a long time your only entertainment was the pleasure of sunsets. I learned this new detail on the morning of the fourth day when you told me:

“I really like sunsets. Let’s go look at one now…”

“But we have to wait…”

“What for?”

“For the sun to set.”

At first you seemed quite surprised, and then you laughed at yourself. And you said to me, “I think I’m still at home!”

Indeed. When it’s noon in the United States, the sun, as everyone knows, is setting over France. If you could fly to France in one minute, you could watch the sunset. Unfortunately France is much too far. But on your tiny planet, all you had to do was move your chair a few feet. And you would watch the twilight whenever you wanted to…

“One day I saw the sun set forty-four times!” And a little later you added, “You know, when you’re feeling very sad, sunsets are wonderful…”

“On the day of the forty-four times, were you feeling very sad?”

But the little prince didn’t answer.

HTML layout and style by Stephen Thomas, University of Adelaide.

Modified by Skip for ESL Bits English Language Learning.