Henry Tandey is, rightly, remembered as an exceptional soldier of the First World War. But his heroism is embroidered by a story that, if true, is one of the great ‘what if’ events of history – moments in time so pivotal that one different decision forever changes the course of history.

Henry, born in 1891, was the son of a stonemason and a laundress. The family appears to have fallen on hard times after Henry’s father, James, quarrelled with his own prosperous father. James is said to have had an evil temper, perhaps influenced by drink. We know Henry spent some time in an orphanage, but we do not know why.

As an adult Henry was only eight and a half stone, and five feet five inches tall. He joined the army in 1910, perhaps to escape his family situation, or the backbreaking, tedious work of a boiler stoker in a Leamington hotel, or perhaps inspired by a sense of adventure. We do not know because Henry kept no diary. If he wrote letters home, none of them survived. Our knowledge of him comes from newspaper interviews, despatches and his medal record.

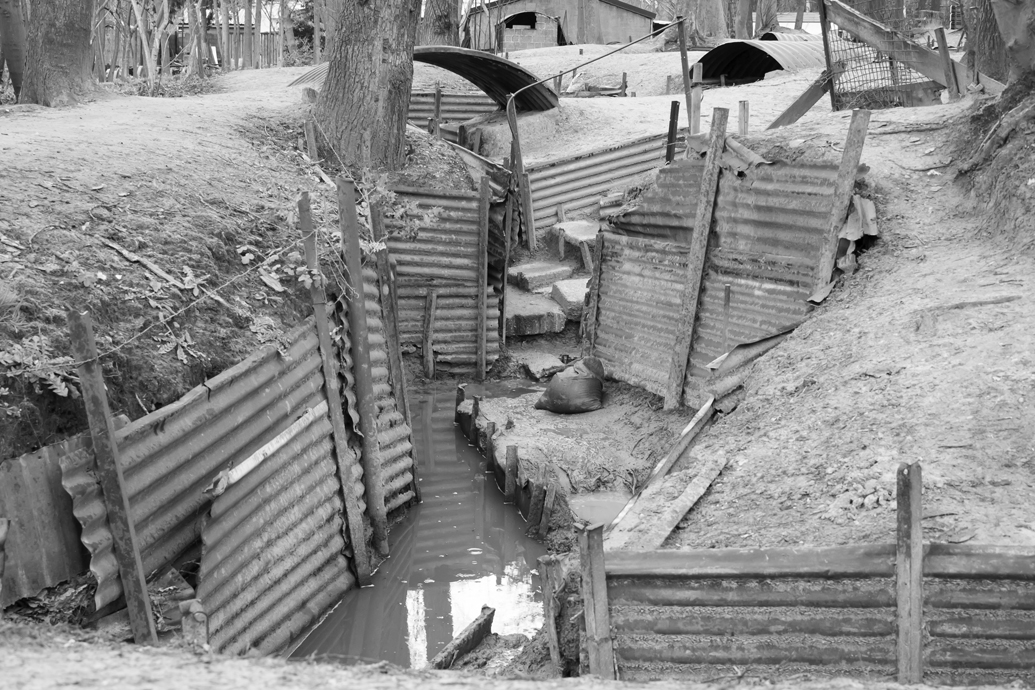

Nicknamed ‘Napper’, he was initially a Private in the Green Howard regiment, which fought in the Battle of Ypres in October 1914. When the Regiment was relieved on 20th October, 700 of 1000 men were dead or badly injured. Meanwhile Henry had rescued some wounded from buildings under shellfire, commenting only: “We were lucky. We managed to get all the wounded back without a casualty.”

By late summer 1918 Henry had been wounded three times and mentioned in army despatches. Then, in an unparalleled burst of heroics by a single soldier, Henry Tandey won the three highest awards for bravery in separate actions in a six-week period.

First he received the Distinguished Conduct Medal. He had been in charge of a reserve bombing party. When soldiers in front of him were held up by German fire, he led two volunteers across open ground to the rear of the enemy. They rushed a machine-gun post, and took twenty prisoners. Next he earned the Military Medal for ‘exhibiting great heroism and devotion to duty’. He ‘went out under most heavy shellfire and carried back a badly wounded man on his back’ and saved three others. The next day he volunteered to lead an attack on a trench.

A German officer ‘shot at him at point-blank and missed. Private Tandey, quite regardless of danger’ drove the enemy away.

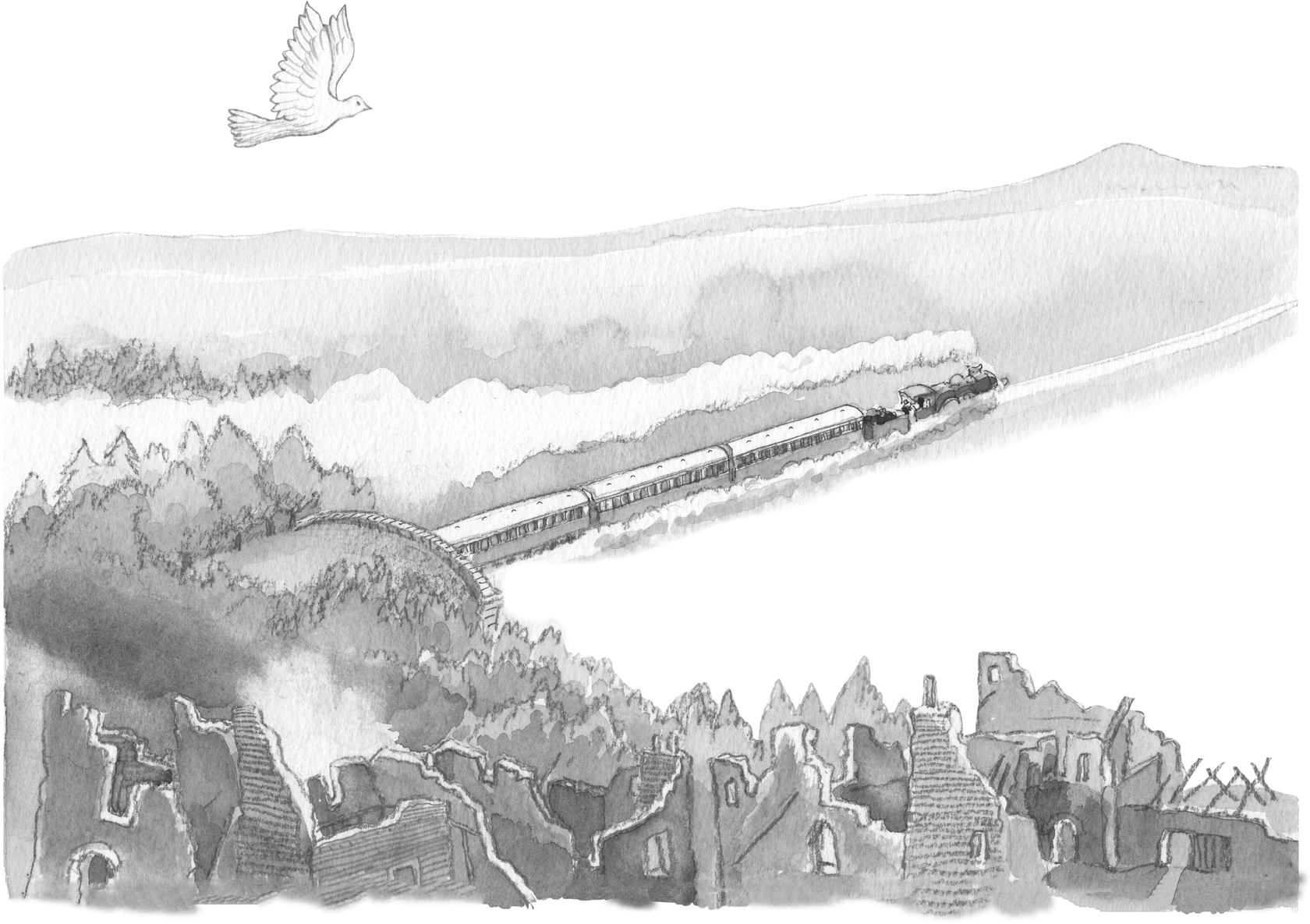

On 28th September 1918, Henry earned the highest British military decoration awarded for valour ‘in the face of the enemy’ – the Victoria Cross. Nearly 9 million British and Commonwealth people served at some stage in the First World War. Only 628 VCs were awarded, mainly to officers. His platoon came under machine-gun attack when attempting to cross a wooden bridge over a canal. Henry crawled forward, replaced broken planks under fire, and led the way across to silence the gun. Later, surrounded and outnumbered, he led eight men in a bayonet charge, driving thirty-seven Germans into the hands of other British troops.

He had earned his three gallantry awards with his new battalion in the Duke of Wellington’s regiment. One senior officer wryly told Henry that his bravery could not adequately be rewarded because he had already won all the gallantry medals available!

After the war Henry stayed on in the army. The only thing of note we know of his post-war service is that he was promoted to Acting Lance Corporal, but reverted to Private within a year at his own request. We don’t know why.

In 1926 he moved back to Leamington, living an undistinguished civilian life. For the next thirty-eight years he was Commissionaire at the Standard Motor Company. But during the Second World War he acted as a part-time Recruiting Officer for the army and as a Fire Warden in Coventry. He married but had no children. He died in December 1977.

Did Henry Tandey have the wounded Adolf Hitler in his rifle sights on the Western Front in the First World War? We will never know for sure. Henry recalled: “I took aim but couldn’t shoot a wounded man, so I let him go.”

Hitler is known to have owned a copy of a painting by Fortunino Matania, commissioned by the Green Howards in 1923. Henry appears in it with an injured comrade over his shoulder.

In 1938 Hitler told British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain why he had the picture depicting Henry: “That man came so near to killing me that I thought I should never see Germany again. Providence saved me from such devilishly accurate fire as those boys were aiming at us.” Hitler asked Chamberlain to convey his thanks to Henry. Henry’s reaction was: “According to them, I’ve met Adolf Hitler. Maybe they’re right, but I can’t remember him.”

In 1940, after the Germans firebombed Coventry, Henry worked to rescue people from the rubble. He was quoted in the Press: “I didn’t like to shoot a wounded man, but if I’d known who this Corporal would turn out to be, I’d give ten years now to have five minutes’ clairvoyance then.”

Some have questioned whether Hitler would really recognise his ‘saviour’, probably mud-spattered, from a distance. Is it credible that he would remember his face twenty years later? But if a British Tommy did spare Hitler’s life when he lay wounded, who better, from Hitler’s point of view, to be fate’s instrument than the most decorated British Private?

The story has been repeated as truth, and denied as often, but Private Henry Tandey will forever be linked with the tag ‘The soldier who didn’t shoot Hitler’.