chapter four

My Father’s Deep Dark Secret

Here I am at the age of nine — Just before all the excitement started and I didn’t have a worry in the world.

You will learn as you get older, just as I learned that autumn, that no father is perfect. Grown-ups are complicated creatures, full of quirks and secrets. Some have quirkier quirks and deeper secrets than others, but all of them, including one’s own parents, have two or three private habits hidden up their sleeves that would probably make you gasp if you knew about them.

The rest of this book is about a most private and secret habit my father had, and about the strange adventures it led us both into.

It all started on a Saturday evening. It was the first Saturday of September. Around six o’clock my father and I had supper together in the caravan as usual. Then I went to bed. My father told me a fine story and kissed me goodnight. I fell asleep.

For some reason I woke up again during the night. I lay still, listening for the sound of my father’s breathing in the bunk above mine. I could hear nothing. He wasn’t there, I was certain of that. This meant that he had gone back to the workshop to finish a job. He often did that after he had tucked me in.

I listened for the usual workshop sounds, the little clinking noises of metal against metal or the tap of a hammer. They always comforted me tremendously, those noises in the night, because they told me my father was close at hand.

But on this night, no sound came from the workshop. The filling-station was silent.

I got out of my bunk and found a box of matches by the sink. I struck one and held it up to the funny old clock that hung on the wall above the kettle. It said ten past eleven.

I went to the door of the caravan. ‘Dad,’ I said softly. ‘Dad, are you there?’

No answer.

There was a small wooden platform outside the caravan door, about four feet above the ground. I stood on the platform and gazed around me. ‘Dad!’ I called out. ‘Where are you?’

Still no answer.

In pyjamas and bare feet, I went down the caravan steps and crossed over to the workshop. I switched on the light. The old car we had been working on through the day was still there, but not my father.

I have already told you he did not have a car of his own, so there was no question of his having gone for a drive. He wouldn’t have done that anyway. I was sure he would never willingly have left me alone in the filling-station at night.

In which case, I thought, he must have fainted suddenly from some awful illness or fallen down and banged his head.

I would need a light if I was going to find him. I took the torch from the bench in the workshop.

I looked in the office. I went around and searched behind the office and behind the workshop.

I ran down the field to the lavatory. It was empty.

‘Dad!’ I shouted into the darkness. ‘Dad! Where are you?’

I ran back to the caravan. I shone the light into his bunk to make absolutely sure he wasn’t there.

He wasn’t in his bunk.

I stood in the dark caravan and for the first time in my life I felt a touch of panic. The filling-station was a long way from the nearest farmhouse. I took the blanket from my bunk and put it round my shoulders. Then I went out the caravan door and sat on the platform with my feet on the top step of the ladder. There was a new moon in the sky and across the road the big field lay pale and deserted in the moonlight. The silence was deathly.

I don’t know how long I sat there. It may have been one hour. It could have been two. But I never dozed off. I wanted to keep listening all the time. If I listened very carefully I might hear something that would tell me where he was.

Then, at last, from far away, I heard the faint tap-tap of footsteps on the road.

The footsteps were coming closer and closer.

Tap … tap … tap … tap …

Was it him? Or was it somebody else?

I sat still, watching the road. I couldn’t see very far along it. It faded away into a misty moonlit darkness.

Tap … tap … tap … tap … came the footsteps.

Then out of the mist a figure appeared.

It was him!

I jumped down the steps and ran on to the road to meet him.

‘Danny!’ he cried. ‘What on earth’s the matter?’

‘I thought something awful had happened to you,’ I said.

He took my hand in his and walked me back to the caravan in silence. Then he tucked me into my bunk. ‘I’m so sorry,’ he said. ‘I should never have done it. But you don’t usually wake up, do you?’

‘Where did you go, Dad?’

‘You must be tired out,’ he said.

‘I’m not a bit tired. Couldn’t we light the lamp for a little while?’

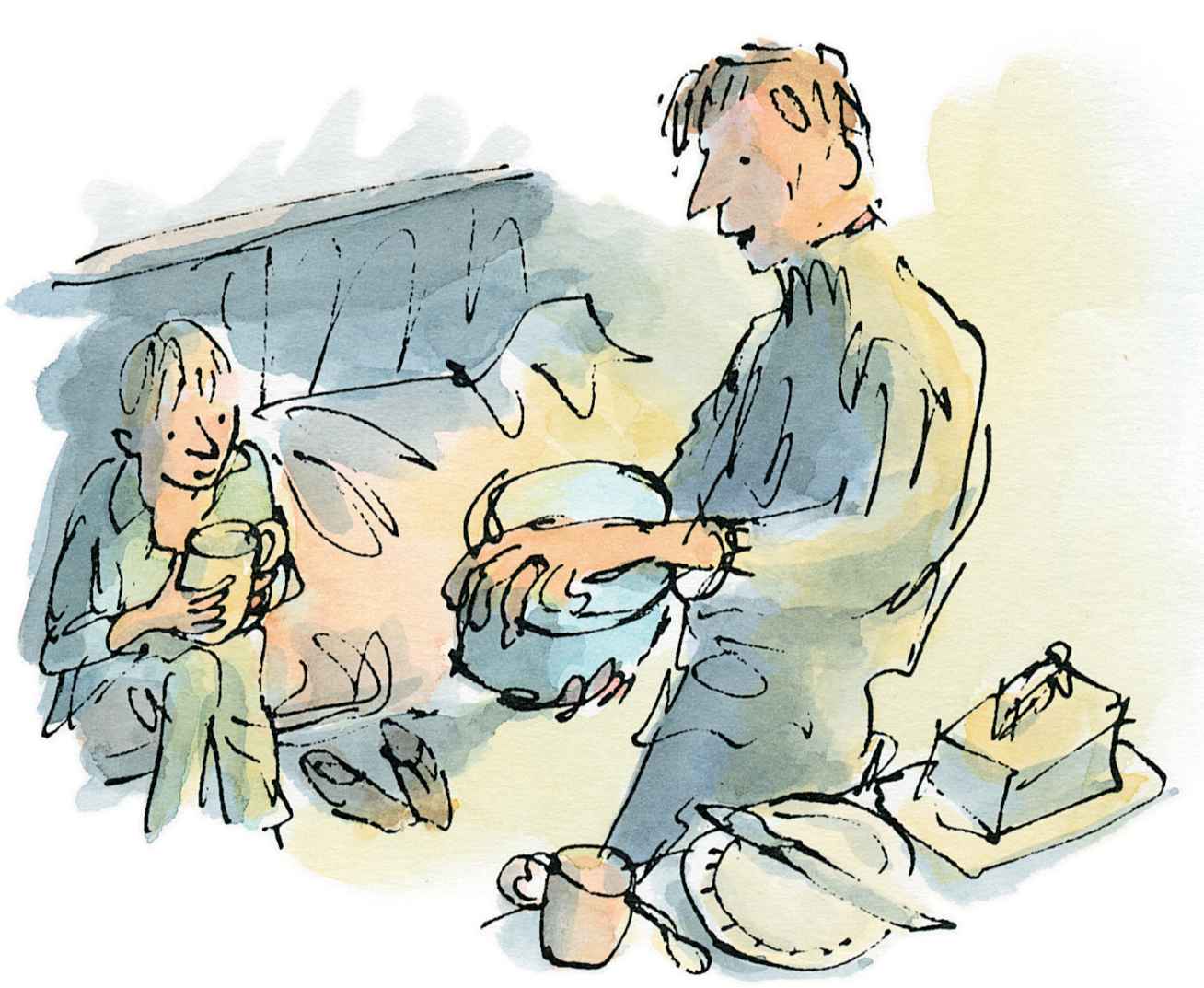

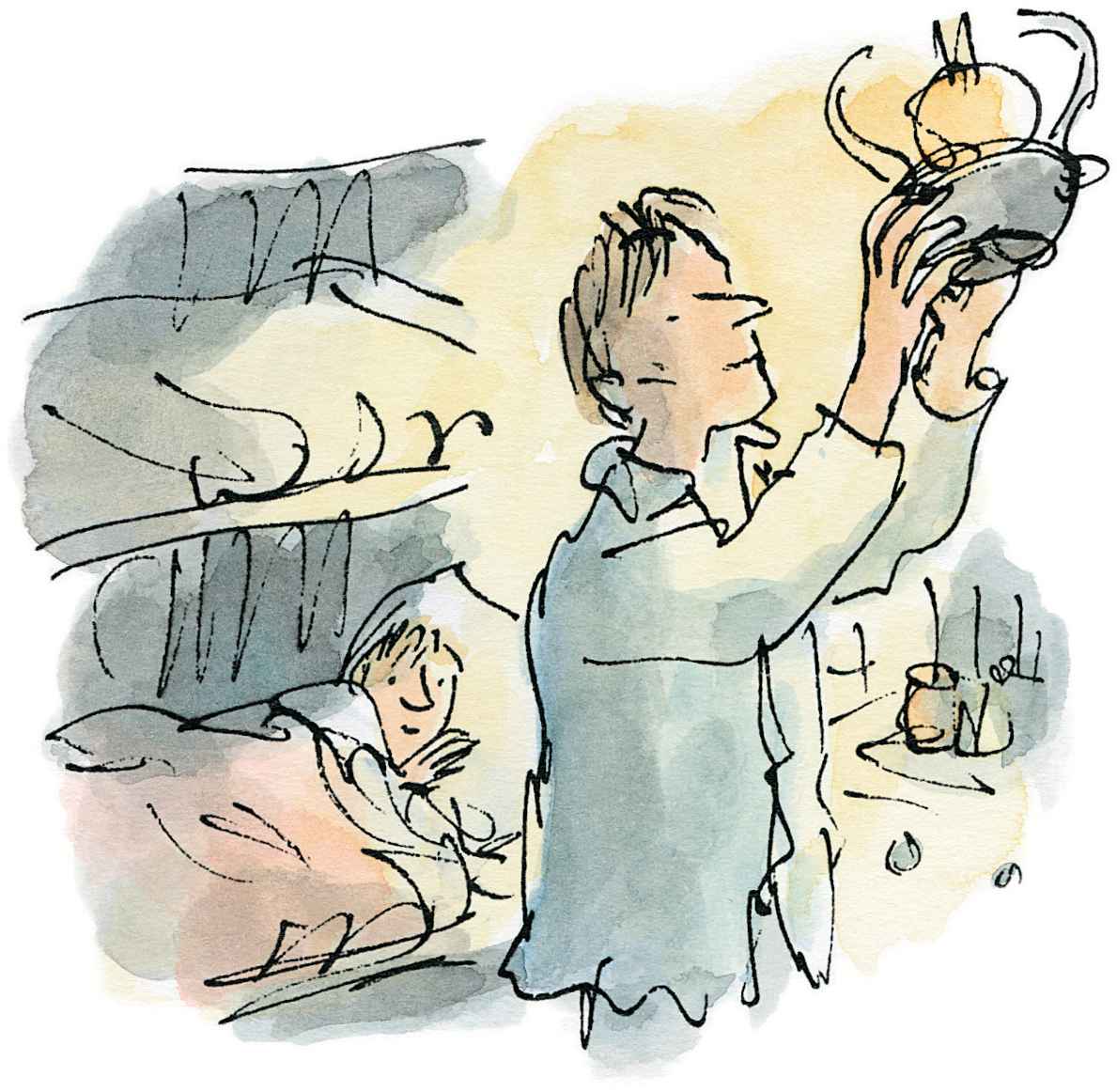

My father put a match to the wick of the lamp hanging from the ceiling and the little yellow flame sprang up and filled the inside of the caravan with pale light. ‘How about a hot drink?’ he said.

‘Yes, please.’

He lit the paraffin burner and put the kettle on to boil.

‘I have decided something,’ he said. ‘I am going to let you in on the deepest darkest secret of my whole life.’

I was sitting up in my bunk watching my father.

‘You asked me where I had been,’ he said. ‘The truth is I was up in Hazell’s Wood.’

‘Hazell’s Wood!’ I cried. ‘That’s miles away!’

‘Six miles and a half,’ my father said. ‘I know I shouldn’t have gone and I’m very, very sorry about it, but I had such a powerful yearning …’ His voice trailed away into nothingness.

‘But why would you want to go all the way up to Hazell’s Wood?’ I asked.

He spooned cocoa powder and sugar into two mugs, doing it very slowly and levelling each spoonful as though he were measuring medicine.

‘Do you know what is meant by poaching?’ he asked.

‘Poaching? Not really, no.’

‘It means going up into the woods in the dead of night and coming back with something for the pot. Poachers in other places poach all sorts of different things, but around here it’s always pheasants.’

‘You mean stealing them?’ I said, aghast.

‘We don’t look at it that way,’ my father said. ‘Poaching is an art. A great poacher is a great artist.’

‘Is that actually what you were doing in Hazell’s Wood, Dad? Poaching pheasants?’

‘I was practising the art,’ he said. ‘The art of poaching.’

I was shocked. My own father a thief! This gentle lovely man! I couldn’t believe he would go creeping into the woods at night to pinch valuable birds belonging to somebody else. ‘The kettle’s boiling,’ I said.

‘Ah, so it is.’ He poured the water into the mugs and brought mine over to me. Then he fetched his own and sat with it at the end of my bunk.

‘Your grandad,’ he said, ‘my own dad, was a magnificent and splendiferous poacher. It was he who taught me all about it. I caught the poaching fever from him when I was ten years old and I’ve never lost it since. Mind you, in those days just about every man in our village was out in the woods at night poaching pheasants. And they did it not only because they loved the sport but because they needed food for their families. When I was a boy, times were bad for a lot of people in England. There was very little work to be had anywhere, and some families were literally starving. Yet a few miles away in the rich man’s wood, thousands of pheasants were being fed like kings twice a day. So can you blame my dad for going out occasionally and coming home with a bird or two for the family to eat?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘Of course not. But we’re not starving here, Dad.’

‘You’ve missed the point, Danny boy! You’ve missed the whole point! Poaching is such a fabulous and exciting sport that once you start doing it, it gets into your blood and you can’t give it up! Just imagine,’ he said, leaping off the bunk and waving his mug in the air, ‘just imagine for a minute that you are all alone up there in the dark wood, and the wood is full of keepers hiding behind the trees and the keepers have guns …’

‘Guns!’ I gasped. ‘They don’t have guns!’

‘All keepers have guns, Danny. It’s for the vermin mostly, the foxes and stoats and weasels who go after the pheasants. But they’ll always take a pot at a poacher, too, if they spot him.’

‘Dad, you’re joking.’

‘Not at all. But they only do it from behind. Only when you’re trying to escape. They like to pepper you in the legs at about fifty yards.’

‘They can’t do that!’ I cried. ‘They could go to prison for shooting someone!’

‘You could go to prison for poaching,’ my father said. There was a glint and a sparkle in his eyes now that I had never seen before. ‘Many’s the night when I was a boy, Danny, I’ve gone into the kitchen and seen my old dad lying face down on the table and Mum standing over him digging the gunshot pellets out of his backside with a potato-knife.’

‘It’s not true,’ I said, starting to laugh.

‘You don’t believe me?’

‘Yes, I believe you.’

‘Towards the end, he was so covered in tiny little white scars he looked exactly like it was snowing.’

‘I don’t know why I’m laughing,’ I said. ‘It’s not funny, it’s horrible.’

‘“Poacher’s bottom” they used to call it,’ my father said. ‘And there wasn’t a man in the whole village who didn’t have a bit of it one way or another. But my dad was the champion. How’s the cocoa?’

‘Fine, thank you.’

‘If you’re hungry we could have a midnight feast?’ he said.

‘Could we, Dad?’

‘Of course.’

My father got out the bread-tin and the butter and cheese and started making sandwiches.

‘Let me tell you about this phoney pheasant-shooting business,’ he said. ‘First of all, it is practised only by the rich. Only the very rich can afford to rear pheasants just for the fun of shooting them down when they grow up. These wealthy idiots spend huge sums of money every year buying baby pheasants from pheasant farms and rearing them in pens until they are big enough to be put out into the woods. In the woods, the young birds hang around like flocks of chickens. They are guarded by keepers and fed twice a day on the best corn until they’re so fat they can hardly fly. Then beaters are hired who walk through the woods clapping their hands and making as much noise as they can to drive the half-tame pheasants towards the half-baked men and their guns. After that, it’s bang bang bang and down they come. Would you like strawberry jam on one of these?’

‘Yes, please,’ I said. ‘One jam and one cheese. But Dad …’

‘What?’

‘How do you actually catch the pheasants when you’re poaching? Do you have a gun hidden away up there?’

‘A gun!’ he cried, disgusted. ‘Real poachers don’t shoot pheasants, Danny, didn’t you know that? You’ve only got to fire a cap-pistol up in those woods and the keepers’ll be on you.’

‘Then how do you do it?’

‘Ah,’ my father said, and the eyelids drooped over the eyes, veiled and secretive. He spread strawberry jam thickly on a piece of bread, taking his time.

‘These things are big secrets,’ he said. ‘Very big secrets indeed. But I reckon if my father could tell them to me, then maybe I can tell them to you. Would you like me to do that?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Tell me now.’

chapter five

The Secret Methods

‘All the best ways of poaching pheasants were discovered by my old dad,’ my father said. ‘My old dad studied poaching the way a scientist studies science.’

My father put my sandwiches on a plate and brought them over to my bunk. I put the plate on my lap and started eating. I was ravenous.

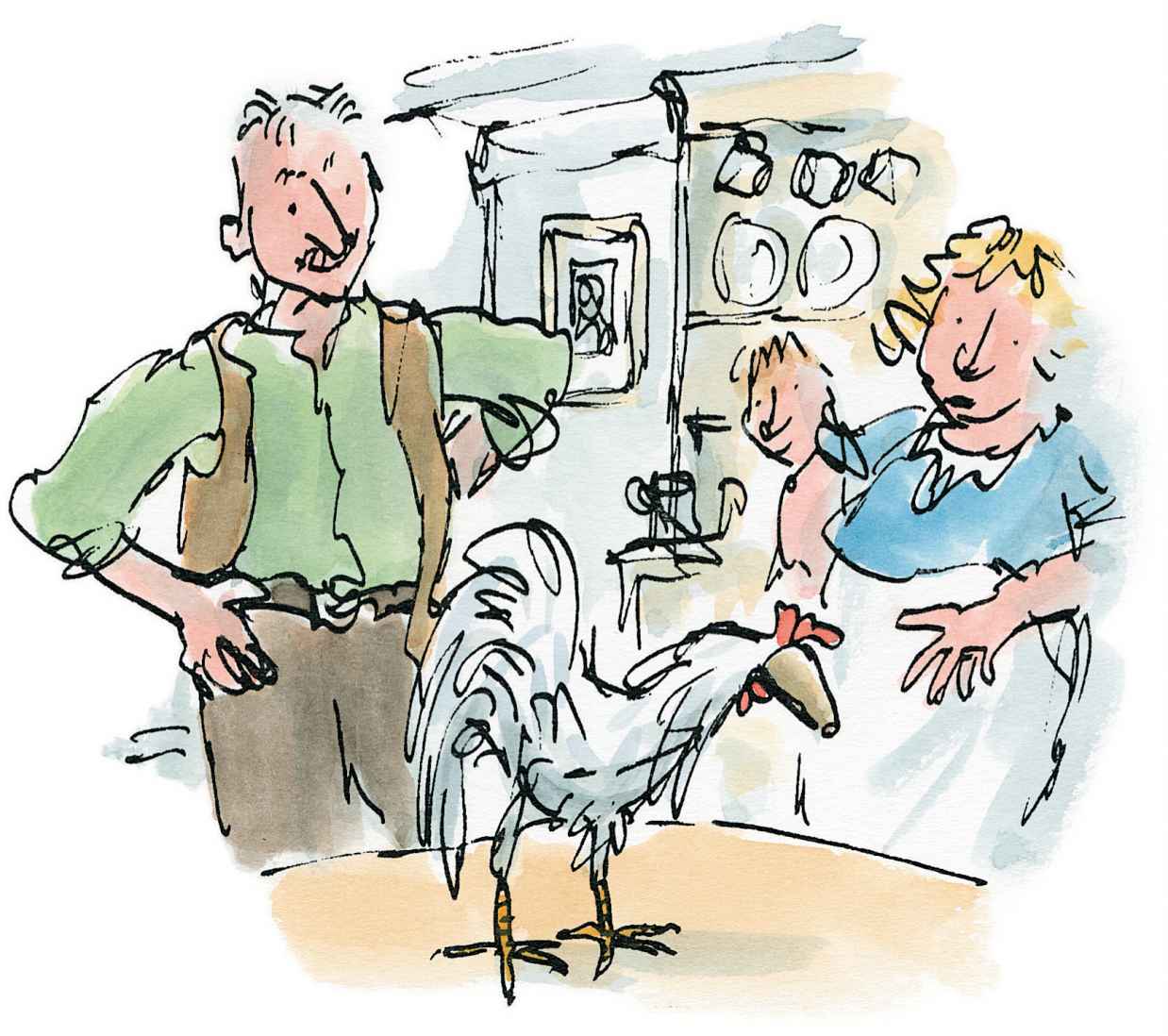

‘Do you know my old dad actually used to keep a flock of prime roosters in the back-yard just to practise on,’ my father said. ‘A rooster is very much like a pheasant, you see. They are equally stupid and they like the same sorts of food. A rooster is tamer, that’s all. So whenever my dad thought up a new method of catching pheasants, he tried it out on a rooster first to see if it worked.’

‘What are the best ways?’ I asked.

My father laid a half-eaten sandwich on the edge of the sink and gazed at me in silence for about twenty seconds.

‘Promise you won’t tell another soul?’

‘I promise.’

‘Now here’s the thing,’ he said. ‘Here’s the first big secret. Ah, but it’s more than a secret, Danny. It’s the most important discovery in the whole history of poaching.’

He edged a shade closer to me. His face was pale in the pale yellow glow from the lamp in the ceiling, but his eyes were shining like stars. ‘So here it is,’ he said, and now suddenly his voice became soft and whispery and very private. ‘Pheasants,’ he whispered, ‘are crazy about raisins.’

‘Is that the big secret?’

‘That’s it,’ he said. ‘It may not sound very much when I say it like that, but believe me it is.’

‘Raisins?’ I said.

‘Just ordinary raisins. It’s like a mania with them. You throw a few raisins into a bunch of pheasants and they’ll start fighting each other to get at them. My dad discovered that forty years ago just as he discovered these other things I am about to describe to you.’

My father paused and glanced over his shoulder as though to make sure there was nobody at the door of the caravan, listening. ‘Method Number One,’ he said softly, ‘is known as The Horse-hair Stopper.’

‘The Horse-hair Stopper,’ I murmured.

‘That’s it,’ my father said. ‘And the reason it’s such a brilliant method is that it’s completely silent. There’s no squawking or flapping around or anything else with The Horse-hair Stopper when the pheasant is caught. And that’s mighty important because don’t forget, Danny, when you’re up in those woods at night and the great trees are spreading their branches high above you like black ghosts, it is so silent you can hear a mouse moving. And somewhere among it all, the keepers are waiting and listening. They’re always there, those keepers, standing stony-still against a tree or behind a bush with their guns at the ready.’

‘What happens with The Horse-hair Stopper?’ I asked. ‘How does it work?’

‘It’s very simple,’ he said. ‘First, you take a few raisins and you soak them in water overnight to make them plump and soft and juicy. Then you get a bit of good stiff horse-hair and you cut it up into half-inch lengths.’

‘Horse-hair?’ I said. ‘Where do you get horse-hair?’

‘You pull it out of a horse’s tail, of course. That’s not difficult as long as you stand to one side when you’re doing it so you don’t get kicked.’

‘Go on,’ I said.

‘So you cut the horse-hair up into half-inch lengths. Then you push one of these lengths through the middle of a raisin so there’s just a tiny bit of horse-hair sticking out on each side. That’s all you do. You are now ready to catch a pheasant. If you want to catch more than one, you prepare more raisins. Then, when evening comes, you creep up into the woods, making sure you get there before the pheasants have gone up into the trees to roost. Then you scatter the raisins. And soon, along comes a pheasant and gobbles it up.’

‘What happens then?’ I asked.

‘Here’s what my dad discovered,’ he said. ‘First of all the horse-hair makes the raisin stick in the pheasant’s throat. It doesn’t hurt him. It simply stays there and tickles. It’s rather like having a crumb stuck in your own throat. But after that, believe it or not, the pheasant never moves his feet again! He becomes absolutely rooted to the spot, and there he stands pumping his silly neck up and down just like a piston, and all you’ve got to do is nip out quickly from the place where you’re hiding and pick him up.’

‘Is that really true, Dad?’

‘I swear it,’ my father said. ‘Once a pheasant’s had The Horse-hair Stopper, you can turn a hosepipe on him and he won’t move. It’s just one of those unexplainable little things. But it takes a genius to discover it.’

My father paused, and there was a gleam of pride in his eyes as he dwelt for a moment upon the memory of his own dad, the great poaching inventor.

‘So that’s Method Number One,’ he said.

‘What’s Number Two?’ I asked.

‘Ah,’ he said. ‘Number Two’s a real beauty. It’s a flash of pure brilliance. I can even remember the day it was invented. I was just about the same age as you are now and it was a Sunday morning and my dad comes into the kitchen holding a huge white rooster in his hands. “I think I’ve got it,” he says. There’s a little smile on his face and a shine of glory in his eyes and he comes in very soft and quick and puts the bird down right in the middle of the kitchen table. “By golly,” he says, “I’ve got a good one this time.”

‘“A good what?” Mum says, looking up from the sink. “Horace, take that filthy bird off my table.”

‘The rooster has a funny little paper hat over its head, like an icecream cone upside down, and my dad is pointing to it proudly and saying, “Stroke him. Go on, stroke him. Do anything you like to him. He won’t move an inch.” The rooster starts scratching away at the paper hat with one of its feet, but the hat seems to be stuck on and it won’t come off. “No bird in the world is going to run away once you cover up its eyes,” my dad says, and he starts poking the rooster with his finger and pushing it around on the table. The rooster doesn’t take the slightest bit of notice. “You can have this one,” he says to Mum. “You can have it and wring its neck and dish it up for dinner as a celebration of what I have just invented.” And then straight away he takes me by the arm and marches me quickly out of the door and off we go over the fields and up into the big forest the other side of Little Hampden which used to belong to the Duke of Buckingham. And in less than two hours we get five lovely fat pheasants with no more trouble than it takes to go out and buy them in a shop.’

My father paused for breath. His eyes were shining bright as they gazed back into the wonderful world of his youth.

‘But Dad,’ I said, ‘how do you get the paper hats over the pheasants’ heads?’

‘You’d never guess it, Danny.’

‘Tell me.’

‘Listen carefully,’ he said, glancing again over his shoulder as though he expected to see a keeper or even the Duke of Buckingham himself at the caravan door. ‘Here’s how you do it. First of all you dig a little hole in the ground. Then you twist a piece of paper into the shape of a cone and you fit this into the hole, hollow end up, like a cup. Then you smear the inside of the paper cup with glue and drop in a few raisins. At the same time, you lay a trail of raisins along the ground leading up to it. Now, the old pheasant comes pecking along the trail, and when he gets to the hole he pops his head inside to gobble up the raisins and the next thing he knows he’s got a paper hat stuck over his eyes and he can’t see a thing. Isn’t that a fantastic idea, Danny? My dad called it The Sticky Hat.’

‘Is that the one you used this evening?’ I asked.

My father nodded.

‘How many did you get, Dad?’

‘Well,’ he said, looking a bit sheepish. ‘Actually I didn’t get any. I arrived too late. By the time I got there they were already going up to roost. That shows you how out of practice I am.’

‘Was it fun all the same?’

‘Marvellous,’ he said. ‘Absolutely marvellous. Just like the old days.’

He undressed and put on his pyjamas. Then he turned out the lamp in the ceiling and climbed up into his bunk.

‘Dad,’ I whispered.

‘What is it?’

‘Have you been doing this often after I’ve gone to sleep, without me knowing it?’

‘No,’ he said. ‘Tonight was the first time for nine years. When your mother died and I had to look after you by myself, I made a vow to give up poaching until you were old enough to be left alone at nights. But this evening I broke my vow. I had such a tremendous longing to go up into the woods again, I just couldn’t stop myself. I’m very sorry I did it.’

‘If you ever want to go again, I won’t mind,’ I said.

‘Do you mean that?’ he said, his voice rising in excitement. ‘Do you really mean it?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘So long as you tell me beforehand. You will promise to tell me beforehand if you’re going, won’t you?’

‘You’re quite sure you won’t mind?’

‘Quite sure.’

‘Good boy,’ he said. ‘And we’ll have roast pheasant for supper whenever you want it. It’s miles better than chicken.’

‘And one day, Dad, will you take me with you?’

‘Ah,’ he said. ‘I reckon you’re just a bit young to be dodging around up there in the dark. I wouldn’t want you to get peppered with buckshot in the backside at your age.’

‘Your dad took you at my age,’ I said.

There was a short silence.

‘We’ll see how it goes,’ my father said. ‘But I’d like to get back into practice before I make any promises, you understand?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘I wouldn’t want to take you with me until I’m right back in my old form.’

‘No,’ I said.

‘Goodnight, Danny. Go to sleep now.’

‘Goodnight, Dad.’

HTML style by Stephen Thomas, University of Adelaide. Modified by Skip for ESL Bits English Language Learning.