January 26

Today after the math final, I ran into Barry in the breezeway. It had to happen sometime, but he didn’t look especially happy to see me, which I thought was unreasonable. He has full custody of Strider. “How come you didn’t keep Strider at your place?” he asked.

I wanted to say I was sorry for all the mean things I had said, but harsh, angry words came out: “Because I’m a rotten kid with a bad attitude.”

Barry looked as if I had hit him. Maybe if I had done better on my math final, I wouldn’t have been in such a bad mood and wouldn’t have sounded so mean.

After school Kevin caught up with me. “How about coming over to my place for something to eat?” he asked.

Why not? Without Strider, I didn’t have anything better to do.

Kevin lives in one of those big old Victorian houses painted in what they call “decorator colors,” which are worth about a million dollars these days. The kitchen was all pink and modern. Kevin opened a door of a huge refrigerator-freezer. “My mother had all our appliances painted this special pink at an auto body shop,” he explained, as if he was apologizing. I had never seen so much frozen food outside a supermarket. “Pizza?” he asked. “I’ll save the beef stroganoff for dinner. Or maybe the chicken cordon bleu. I’m not into Weight Watchers.”

“Pizza’s great.” I was puzzled. “Doesn’t your mother cook?”

Kevin shoved the pizza into the microwave. “She never cooks. We just choose whatever we want and nuke it in the microwave.”

While we ate the Pizza, I learned a lot about Kevin, who seemed to need someone to talk to. His father is rich and lives in San Francisco on Nob Hill, or in his condo in Hawaii, and is mad at Kevin because he couldn’t get into prep school when practically everyone in the family back to Adam and Eve has gone to prep school. Kevin was mad at his father for divorcing his mother for a younger woman in the midst of the entrance exams he had to take. Kevin explained that his mother received lots of alimony, and the housekeeper who came in every morning didn’t like him to mess up the kitchen. He wished he had gone out for cross-country because it would give him something to do.

I’m ashamed to say Kevin’s problems made me feel a little better about mine.

When I told Mom I had a new friend who wasn’t very happy, she asked, “What’s his problem?”

“He’s rich.”

Mom laughed and said she wished she had the same problem, but after seeing how Kevin lives, I don’t think his being rich is so funny.

Mom said, “Maybe we should ask him over for dinner sometime when I have a day off.” Then she added, “Unless you are ashamed of the way we live.”

I have never been ashamed, but now I wonder if I’m going to be.

February 13

Today Kevin and I turned out for track. Mr. Kurtz, the coach, gave us a pep talk about the importance of taking part and doing the best we can. He said it’s not the winning, it’s the competing that’s important. He stressed looking for improvement within ourselves. That means I’ll have to start chipping away at my bad attitude.

Across the playing field I could see Geneva, arm and leg extended, red hair flying, still working at clearing those hurdles. She is improving, which probably means she has the right attitude.

The varsity team calls Mr. Kurtz “Coach,” but most of us younger kids don’t feel we know him that well. He watched the freshmen and sophomores work out. Afterward, as we headed for the locker room, Mr. Kurtz put his hand on my shoulder and said, “I have a feeling you’re going to make a real contribution to the team. Stick with it.” This surprised me. With Barry and Strider so heavy on my mind, my feet felt heavy, too.

To Kevin he said, “With those long legs, you should do well.”

February 14

On a scale of one to ten, today was about fifteen. When I came home from school, Strider was sitting by the front door! When he saw me, he came running, jumped up, and licked my face. That long wet tongue felt good.

“Strider!” was all I could say. “Strider!” He wriggled all over, he was so glad to see me.

I looked for his leash, but it was nowhere around. Neither was his posture dish. That meant one thing. Strider had come on his own. The Brinkerhoffs’ fence wasn’t so high he couldn’t get over it if he really wanted to.

I felt great. Strider wanted me. I took him inside and fed him in a plain dish. His slurp-slobber sounded good, just like old times.

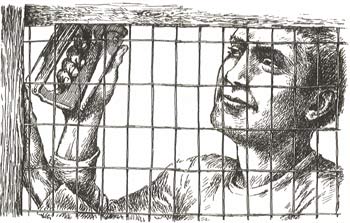

And then the telephone rang. My heart dropped so far it practically bounced on the floor because I had a feeling Barry was calling. He was.

“Is Strider there?” Barry sounded anxious.

“Yes,” I said. “Want to speak to him?”

“Wise guy,” said Barry. “What’s he doing there? Did you come and get him?”

I pointed out to Barry that if I had taken Strider, I would have taken his leash and posture dish, too, and said, “Coming back was Strider’s idea. He came on his own.” When Strider heard his name, he rested his head on my knee.

“That’s what I figured,” said Barry, “but I wanted to be sure no one had stolen him.”

We were both silent. I could hear the little sisters shrieking in the background, so I knew he had not hung up on me.

Finally Barry said, “You didn’t need to give up custody.”

“I guess I was upset about a lot of things,” I admitted, “so I said things I was sorry for.” Maybe it’s easier to talk about some things over the telephone, rather than face to face.

“That’s what Mom said.” Barry was silent a moment while I thought, Thank you, Mrs. Brinkerhoff, for understanding.

Finally Barry said, “You keep him, and I will be his friend. He has shown he likes you best, and I know you exercise him more than I do. Anyway, I don’t like to wash his dish, and he makes my sisters’ cats nervous.”

“Gee, Barry…” I was so grateful I could hardly talk.

“That’s okay.” Barry understood.

When I got hold of myself, I felt I had to mention one worry. “If I keep him, people will laugh and say they knew we couldn’t manage joint custody. You know how they talked.”

“Yeah,” agreed Barry. “They’re saying it already. There ought to be some way around all their stupid remarks they think are so funny.”

In our silence, I had an idea, a really brilliant idea. “When Mom and Dad got divorced, I heard something about if a kid is old enough and smart enough to form an intelligent preference, he can have something to say about custody. Or something like that. I know I am right about the intelligent preference bit.”

“Hey, that sounds great!” Barry was excited. “We can just say Strider is now mature enough to express an intelligent preference, and he decided to live with you.” We laughed like old times.

“After all, how many dogs are mature enough to read?” I asked, and we laughed some more. Then I had another thought. “The trouble is, I’m going out for track. I can exercise him in the morning, but if I leave him inside during the day, he eats the rug.”

“No problem,” said Barry. “Just leave him in our yard like always, and I’ll exercise him during track season. I need to stay in shape for football next year.”

In a little while, Barry came down the path with Strider’s leash and posture dish. We didn’t have to say we were glad to be friends again. We both knew it. I also knew, but would never say, that Barry is relieved to be rid of the entire responsibility of Strider. I don’t mind washing his dish.

I hugged my dog. Both halves of him are mine!

March 1

The first of the month, I was about to hide Strider in the bathroom before Mrs. Smerling could come demanding rent money. Suddenly I changed my mind. Calling this place a shack gets on Mom’s nerves; sneaking around worrying about rent being raised because of my dog gets on my nerves.

Mrs. Smerling’s thong sandals came slapping down the path; I opened the door and, with Strider by my side, handed her the rent check Mom had waiting on the chair by the door. “Mrs. Smerling, Strider is my dog now,” I informed her. “He has expressed an intelligent preference to live with me instead of living in joint custody.”

Mrs. Smerling looked surprised and said, “So?”

“So do you object to my keeping a dog?” I felt a little sick, as if Mom and I were about to become street people.

“You haven’t fooled me for one minute,” said Mrs. Smerling. “I haven’t objected yet.”

Whew! I decided to press my luck. “Are you planning to raise our rent because of him?”

“Not unless I have to clean up dog messes.”

“You won’t,” I promised. “I’ll get a pooper-scooper or an old license plate or something.”

“You’re a good kid, Leigh,” Mrs. Smerling said. She started to leave, then turned back and asked, “Don’t you need a fence for your dog?”

Had she noticed the chewed rug? Probably. “A fence would help,” I had to agree.

“So build one,” said Mrs. Smerling. “A good fence would add to the value of my property.” She went slapping down the path.

Drying her hair with a towel, Mom came into the room. She was laughing. “Leigh, you amaze me. How did you get away with that?”

I shrugged. “By being the man in the family.” Now maybe Mom won’t miss her little boy so much.

Then Mom frowned. “It seemed to me Mrs. Smerling made a fence sound compulsory.”

That was just what I was beginning to think.

March 2

A fence, a fence, my kingdom for a fence, as Shakespeare would say.

The yard already has a fence, overgrown with bushes, along one side and across the back. That leaves the side along the gas station and the space from there to the apartment house in front of our cottage. Barry and Kevin offered to help me build a fence from packing crates from the furniture store down the street, but I have a feeling Mrs. Smerling wouldn’t think that kind of fence would increase the value of her property.

Kevin offered to pay for a fence. I couldn’t let him do that, and Mom would never allow it. Barry says his father would build me a fence if we asked him. He has all the tools. This was nice of Barry, but I couldn’t accept that offer either. I have my pride, even if I don’t have enough money for a fence.

Problem solving, and I don’t mean algebra, seems to be my life’s work. Maybe it’s everyone’s life’s work.

March 12

I got to thinking: if Barry’s father would be willing to build Strider a fence, what about my father? Without consulting Mom, I phoned him at his trailer in Salinas. “Dad, would you build me a fence?” No use wasting words.

“Where at?” He sounded surprised. I explained. “Sure, no problem,” he agreed and didn’t waste time. That same evening he drove over to take measurements by the light from the gas station next door.

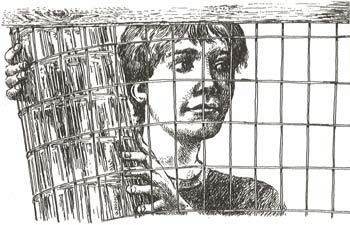

A few days later, when I came home from school, I found evenly spaced four-by-fours six feet high set in concrete which had only begun to harden. I pressed Strider’s paw into it by the post where the gate will go. Now my dog is immortalized.

Yesterday, when Strider and I returned from my mopping job, I saw Dad’s pickup loaded with lumber, hog wire, a gate already built, and Bandit. Dad was talking to Mom while Mrs. Smerling watched out the window.

“Come on, Leigh. Pitch in,” said Dad. Mom said she had a lot of errands to do and wouldn’t be home till after work. I think she was just making excuses not to be around Dad.

Dad and I went to work nailing stringers in place. I felt good working with Dad, getting sweaty, while Strider sat watching. Bandit just stayed in the truck.

About the time all the stringers were in place, a lady drove up in a red Toyota, got out, and walked up the path. “Hi, Bill,” she said. “How’s it going?”

Dad kissed her and said, “Great. Alice, this is my son, Leigh.”

I remembered to wipe my hand on the seat of my pants, hold it out, and say, “How do you do?” which wasn’t easy because I was so surprised. Alice looked a little older than Mom, and plumper, but she was attractive. Nothing flashy.

“Hello, Leigh,” she said as if she liked me. She scratched Strider behind his ear when he got up to sniff her over. She said she had errands to do and “just thought I would come by to see how the fence was coming along.” Then she drove off.

Suspicious, I asked, “She come to look me over?”

Dad grinned. “Could be.”

“You serious?”

“Maybe.”

“Any kids?”

“Girl in college.”

Old Wounded-hair wouldn’t approve of this conversation. Dad and I seemed unable to talk in complete sentences.

By midafternoon, without stopping to eat, we had stapled the hog wire to the fence posts, hung the gate, and screwed the latch in place. Strider had a neat six-foot fence that should increase the value of Mrs. Smerling’s property. I thanked Dad, who said, “That’s okay. Let’s go get something to eat.”

We washed around the edges and, leaving Strider looking surprised behind his fence, went off to a Mexican restaurant where we both ordered the special Mexican platter with enchiladas, chiles rellenos, tacos, refried beans, and rice. Dad had a beer, and I asked for buttermilk, which tasted good with Mexican food.

We ate in silence for a while. Then Dad rolled a tortilla, looked straight at me, and said, “How come you never asked me for anything before? It always seemed like you wanted a ride in my rig, but you didn’t want me.”

I was stunned and embarrassed by this speech. Dad was never good at expressing his feelings. Maybe I wasn’t either. Wanted him! For a long time after the divorce, I had ached for him.

“I guess I felt you had abandoned me,” I confessed, “even if you did let me ride with you sometimes.”

Dad sighed. “I know I’ve let you down, but I’ve missed you, kid, and I’ve grown up a lot in the last couple of years.”

This time I didn’t get angry the way I used to when Dad called me a kid. Now “kid” sounds like an affectionate nickname, not a substitute for my real name, which I used to think he had forgotten.

Dad and I had our first real conversation. I didn’t mind so much when he began to talk about my future, although I would just as soon he hadn’t brought it up. As he dropped me off at the cottage, he said, “We’ll have to build Strider a doghouse.”

When Mom came home from work, I woke up and told her about Alice. “Good,” she said, and meant it. “I’m really glad he’s found someone.” Maybe, because he lives so close, she was afraid he would hang around here because he was lonesome. Coming over to build a doghouse is different.

March 13

Now that I have solved a few of my problems, but not my future, my feet feel light. I run faster, as if I had wings on my heels like the Greek god Mercury in florists’ ads, except Mercury didn’t have to wear track shoes because his feet didn’t touch the ground.

Coach wants me to run the eight hundred meters and Kevin to run the fifteen hundred meters. Geneva no longer knocks over so many hurdles.

My days whiz by. Barry runs with Strider after school and brings him to the track for me to take home.

While I mop, I study my Spanish: Esta mesa es de madera. Está sobre la mesa.

While I run, I think about the short stories we are studying. This semester’s English teacher, Mr. Drexler, isn’t a teacher who pounces on kids trying to look inconspicuous and demands, “What is the theme of this story?” He asks, “Would someone like to volunteer the theme of this story?” because he knows themes are nobody’s favorite question. I like to volunteer, even if I am sometimes wrong.

March 14

Today I did a stupid thing. I watched Geneva run the hurdles, and afterward, when she was walking to cool down, I got up my courage to walk beside her. (Not too close.)

“Hi, Leigh,” she said.

“Good work,” I said, “but did you ever think your hair might offer wind resistance? Maybe if you tied it back, it would help your time.” Then I wondered if she would think I had said the wrong thing.

She put her hand to her hair, which curled around her face in damp tendrils. “I never thought of that,” she admitted. “Thanks for the tip.”

“Your hair is sure pretty,” I said to make sure she wouldn’t feel I was criticizing. For some reason I thought of Barry’s grandmother’s beautiful needle-art knitting with soft, colorful yarns. Without thinking, I said, “Your hair would look nice knit into a sweater.”

Geneva stopped and faced me with her hands on her hips. “Leigh Botts, you’re really weird!” She turned and ran down the track.

I felt like bagging my head.

March 15

Track, track, track.

School is more interesting this semester, especially the study of short stories in English. I study, fall asleep, get up, run with Strider, work out after school. Friday afternoon the team competes against King City in our first meet of the season.

I think of the Olympics on TV: trumpets, sunshine, flags, great-looking athletes from all over the world, the winners struggling to hold back tears when ribbons holding medals are placed over their heads while their national anthems are played and the crowd cheers.

Next to exercising Strider, working out is the best part of the day. I love the grit of my spikes biting into our sandy track, the exhilaration I feel after I run, the satisfaction of cutting down my time. Kidding around in the locker room is fun, even when someone tries to snap a towel at me. I am proud of my gold and red sweats. Geneva smiles and waves at me across the track, so she can’t be angry. Barry meets me at the track with my dog.

Sometimes Kevin comes home with me, or we both go to Barry’s house. The first time Kevin came here, he blurted, “You mean you live here?” Then he apologized for being rude. Kevin has manners.

“Sure,” I said. “It keeps the rain off.”

Now Kevin likes to come here rather than be alone in a big house while his mother is out playing bridge or, as he says, playing at being an interior decorator. Sometimes we cook. I taught him to make an omelette. If he knows Mom will be home for supper, he wears a necktie! Mom says he’s a nice boy with an aura of sadness about him, which must be the sort of boy I was when I was in the sixth grade and my parents were just divorced.

Now I have three friends: Barry, Geneva, and Kevin. I am part of the track crowd. I fit in. I belong.