He and Big Mama Thornton were taking a break backstage when it happened. The dance floor was covered with Mexican and black people, a big haze of cigarette and reefer smoke floating over their heads in the spotlights. White people were up in the balcony, mostly low-rider badasses wearing pegged drapes and needle-nose stomps and girls who could do the dirty bop and manage to look bored while they put your flopper on autopilot. Then we heard it, one shot, pow, like a small firecracker. Johnny's dressing-room door was partly opened and I swear I saw blood fly across the wall, just before people started running in all directions.

Everyone said he had been showing off with a .22, spinning the cylinder, snapping the hammer on what should have been an empty chamber. But R&B and rock 'n' roll could be a dirty business back then, get my drift? Most of the musicians, white and black, were right out of the cotton field or the Assembly of God Church. The promoters and the record company executives were not. Guess whose names always ended up on the song credits, regardless of who wrote the song?

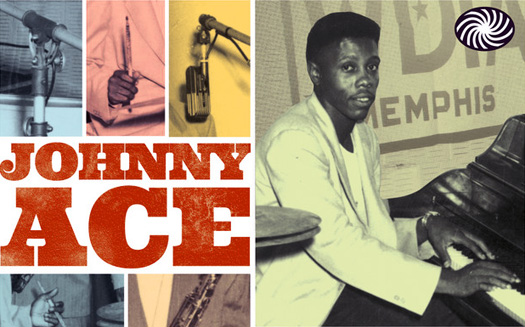

But no matter how you cut it, on Christmas night, 1954, Johnny Ace joined the Hallelujah Chorus and Eddy Ray Holland and I lost our chance to be the rockabillies who integrated R&B. Johnny had promised to let our band back him when he sang "Pledging My Love" that night. In those days Houston wasn't exactly on the cutting edge of the civil rights movement. We might have gotten lynched, but it would have been worth it. Listen to "Pledging My Love" sometime and tell me you wouldn't chuck your box in the suburbs and push your boss off a roof to be seventeen and hanging out at the drive-in again.

Nineteen fifty-four was the same year we met the kid from Mississippi Eddy Ray used to call the Greaser*, because that boogie haircut of his looked like it had been hosed down with 3-in-One oil. But teenage girls went apeshit when the Greaser came onstage at the Louisiana Hayride, screaming their heads off, throwing their panties at him, crushing the roof of his Caddy to get into his hotel window, tearing out each other's hair over one of his socks. I even felt sorry for him. When they got finished with him, he usually looked like he'd been shot out of a cannon. [*Elvis Presley]

"I think the guy is a spastic. It's not an act," Eddy Ray said.

"Johnny Ray wears a hearing aid onstage. Fats Domino's mother probably thought she gave birth to a bowling ball," I said. "Jerry Lee looks like somebody slammed a door on his head. The Greaser played on Beale Street with Furry Lewis and Ike Turner. Give the guy some credit."

"Shut up, R.B.," Eddy Ray said.

I didn't argue. I knew Eddy Ray didn't carry grudges or envy people. Things just weren't going well for our band, that's all. The beer-joint circuit was full of guys like us, most of them talented and not in it for the money, either. On average the total pay wasn't more than fifty bucks a gig. The whole band usually traveled and slept in a couple of cars with the drums in the trunk and the other instruments roped on top. We lived on Vienna sausage, saltine crackers, and Royal Crown Colas, and brushed our teeth and took our baths in gas station lavatories.

The big difference with our group was Eddy Ray. He played boogie-woogie and blues piano and a Martin acoustic guitar and could make oilfield workers wipe their eyes when he sang "The Wild Side of Life."

Girls dug him, too. He had a profile like the statues of those Greek heroes, with the same kind of flat chest and stomach muscles that looked like rolls of quarters and smooth skin that had never been tattooed. Not many people knew that Eddy Ray still heard bugles blowing in the hills south of the Yalu River. I was at the Chosin Reservoir, too, but Eddy Ray got grabbed and spent over two years at a prisoner-of-war camp in a place called No Name Valley. He always said four hundred of our soldiers got moved up into Red China, where they were used in medical experiments. I could tell when he was thinking about it because the skin around his left eye would twitch like a bumblebee was fixing to light on it.

So why would a stand-up guy like Eddy Ray be bothered by a kid from Tupelo, Mississippi?

Remember when I mentioned the gals who could start your flopper flipping around in your slacks like it has a brain of its own? This one's nickname was the Gin Fizz Kitty from Texas City. She had gold hair, cherry lipstick, and blue eyes that could look straight up into yours like you were the only guy on the planet. When Eddy Ray and I first saw her, six months before we were supposed to have our breakthrough moment with Johnny Ace, she was singing at a roadhouse called Buster's in Vinton, Louisiana. Outside, the heat had started to go out of the day, and through the screens we could see a lake and beyond it a red sun shining through a grove of live oak trees. We were at the bar, drinking long-necked Jax and eating crab burgers, a big-bladed window fan blowing cool in our faces, but Eddy Ray couldn't concentrate on the fine evening and the good food and the coldness of the beer. His attention was fixed on the girl at the microphone and the way her purple cowboy shirt puffed and dented and changed colors in the breeze from the floor fan, the way she closed her eyes when she opened her mouth to sing, like she was offering up a prayer.

"What a voice. I'm going to ask her over," he said.

"I think I've seen her before, Eddy Ray," I said.

"Where?"

I looked at his expression, the sincerity in it, and wanted to kick myself. "At the Piggly Wiggly in Beaumont," I said.

"Thanks for passing that on, R.B."

He invited her to have a beer with us during her break. She didn't drink beer, she said. She drank gin fizzes. And she drank more of them in fifteen minutes than I ever saw anyone consume in my life. I thought we were going to get hit with a bar bill that would bankrupt us for the next month. But it all went on her tab, which told me she had a special relationship with the owner. When Eddy Ray went to the can, she smiled sweetly and asked, "You got some reason for staring at me, R.B.? I know you from somewhere?"

"No, ma'am, I don't think so," I replied, my face as blank as a shingle.

"If you got a haircut and tucked in your shirt and pulled up your britches, you'd be right handsome. But don't stare at people. It's impolite."

"I won't, I promise," I said, and wondered what we were fixing to get into.

I soon found out. Kitty Lamar Rochon's voice could make the devil join the Baptist Church. When she and Eddy Ray did a number together, the dancers stopped and gathered around the bandstand as if angels had descended into their midst. It didn't take long for Eddy Ray to develop a very strong attraction for the Gin Fizz Kitty from Texas City. No, that doesn't describe it. It was more like he'd been run over by a train. So how do you tell your best friend he's been suckered and poleaxed by the town pump? Nope, "town pump" isn't the right term, either.

There was a chain of whorehouses that ran all the way along the Texas and Louisiana coast, all of them run by two Italian crime families that operated out of Galveston and New Orleans. How does a girl as pretty as Kitty Lamar end up in a cathouse? Believe it or not, most of the girls in those places were good-looking, some of them even beautiful. It was the times. Poor people didn't always have the choices they got today. Don't ask me how I know about this stuff, either.

So I didn't say diddly-squat to Eddy Ray. But, man, was it eating my lunch. For example, one week after Johnny Ace capped himself (or had somebody do it for him), we were blowing down the road in Eddy Ray's '49 Hudson, headed toward our next gig, a town up in Arkansas that was so small it was located between two Burma Shave signs. Kitty Lamar was lying down in the backseat, airing her bare feet, with the toenails painted red, out the window. She was popping bubble gum and reading a book on, get this, French existentialism, and commenting on it while she turned the pages. Then out of nowhere she lowered her book and said, "I wish you'd stop giving me them strange looks, R.B."

"Excuse me," I said.

"What's with you two?" Eddy Ray said, one hand on the wheel, a deck of Lucky Strikes wrapped in the sleeve of his T-shirt.

The previous night at the motel I'd heard her talking on the phone to the Greaser. It was obvious to me Kitty Lamar and the Greaser had known each other for some time and I'm talking about in the biblical sense. Eddy Ray had evidently decided to let bygones be bygones, but in my opinion she kept doing things that were highly suspicious. For example again, she loved fried oysters and catfish po'boy sandwiches. Then we'd be playing a gig around Memphis and she wouldn't touch a fish or shrimp or oyster dinner with a dung fork. Why is this significant? The Greaser was notorious for not allowing his punch of the day to eat anything that smelled of fish. Is that sick or what?

"Why don't we stop at that seafood joint up the road yonder and tank down a few deep-fried catfish sandwiches?" I said. "I know Kitty Lamar would dearly appreciate one."

She gave me a look that would scald the paint off a battleship.

"It doesn't matter to me one way or another, because I don't eat seafood this far inland," she said, her nose pointed in her book.

"Why is that, Kitty Lamar?" I asked, turning around in the seat, my face full of interest.

"Because that's how you get ptomaine poison. Most people who went past the eighth grade know that. Have you ever applied for a public library card, R.B.? When we get back to Houston, I'll show you how to fill out the form."

"Am I the only sane person in this car?" Eddy Ray said.

On Saturday night we played a ramshackle dance hall in the Arkansas Delta, just west of the Mississippi Bridge. Snow was blowing and Christmas lights were strung all over the outside of the building, so that the place glowed like a colored jewel inside the darkness. The tables and bar and dance floor were crowded with people who believed the live country music shows from Shreveport, Nashville, and Wheeling, West Virginia, represented a world of magic and celebrity and wealth that was hardly imaginable to them. Probably everybody in our band had grown up chopping cotton and picking ticks off themselves in a sluice of well water from a windmill pump, but onstage, here in the Delta, or a hundred places like it, we were sprinkled with stardust and maybe even immortality.

You know the secret to being a rockabilly or country music celebrity? It's not just the sequins on your clothes and the needle-nosed, mirror-shined boots. Your music has to be full of sorrow, I mean just like the blood-flecked, broken body of Jesus on the Cross. When people go to the Assembly of God Church and look up at that Cross, the pain they see there isn't in Jesus' body, it's in their own lives. I'm talking about droughts, dust storms, mine blowouts, black lung disease, or pulling cotton bolls or breaking corn till the tips of their fingers bleed. I went to school with kids who wore clothes sewn from Purina feed sacks. Eddy Ray was one of them. What I'm trying to say is we come from a class of people who think of misery as a given. They just want somebody who's had a degree of success to treat them with respect.

We'd all been in the dumps since Johnny died, me more than anybody, although I couldn't tell you exactly why. It was like our innocence had died with him. In fact, I felt sick thinking about it. I'd look over at the Gin Fizz Kitty from Texas City and hear that peckerwood accent, which sounded like somebody pulling a strand of baling wire through a tiny hole in a tin can, and I'd flat want to lie down on the highway and let a hog truck run over my head. A group of Yankees by the name of Bill Haley and the Comets were calling themselves the founders of rock 'n' roll and we were playing towns where families in need of excitement drove out on the highway to look at the new Coca-Cola billboard. And Johnny was dead, maybe not by his own hand, and his friends had gotten a whole lot of gone between him and them.

But that night in the Arkansas Delta, with the dancers shaking the whole building, it was like we were young again, unmarked by death, and the earth was green and so was the country and wonderful things were about to happen for all of us. We didn't take a break for two hours. When Eddy Ray ripped out Albert Ammons's "Swanee River Boogie" on the piano, the place went zonk. Then we kicked it up into E-major overdrive with Hank's "Lovesick Blues" and Red Foley's "Tennessee Saturday Night," Eddy Ray and Kitty Lamar sharing the vocals. I got to admit it, the voices of those two could have started a new religion.

The snow stopped and a big brown moon came up over the hills, just as Guess Who walked in. You got it. The Greaser himself, along with Carl Perkins and Jerry Lee, all three of them decked out in sport coats, two-tone shoes, and slacks with knife-edged creases, their open-neck print shirts crisp and right out of the box. They sat at a front-row table and ordered long-neck beers and French-fried potatoes cooked in chicken fat. In less than two minutes half the women in the place were jiggling and turning around in their chairs like they'd just been fed horse laxative.

"What's he doing here?" Eddy Ray said.

Duh, I thought. But all I said was, "He's probably just tagging along with Jerry Lee and Carl. Sure is a nice night, isn't it?"

Then Kitty Lamar came back from the ladies' can and said, her eyes full of pure blue innocence, as though she had no idea the Greaser was going to be there: "Look, all the fellows from Sun Records are here. Are you gonna introduce them, Eddy Ray?"

Eddy Ray looked through the side window at the moon. The hills were sparkling with snow, the sky black and bursting with stars. "I haven't given real thought to it," he said. "Maybe you should introduce them, Kitty Lamar. Maybe you could sing a duet. Or maybe even do a three-or a foursome."

"How'd you like to get your face slapped?" she replied, chewing gum, rolling her eyes.

Eddy Ray pulled the mike loose from the stand, kicking a lot of dirty electronic feedback into the speaker system, like fingernails raking down a blackboard. His cheeks were flushed with color that had the irregular shape of fire, his eyes dark in a way I had not seen them before. He asked Carl and Jerry Lee and the Greaser to stand up, then he paused, as though he couldn't find the proper words to say. The whole joint was as quiet as a church house. I could feel sweat breaking on my forehead, because I knew the pain Eddy Ray was experiencing, and I knew the memories from the war that lived in his dreams, and I'd always believed part of him died in that prisoner-of-war camp south of the Yalu. I believed Eddy Ray carried a stone bruise in his heart, and if he felt he had been betrayed by the people he loved, he was capable of doing bad things, maybe not to others, but certainly to Eddy Ray. It wasn't coincidence that he and Johnny Ace had been pals.

The floor lights on the stage were wrapped with amber and yellow cellophane, but they seemed to burn red circles into my eyes. Jerry Lee and Carl were starting to look uncomfortable and the crowd was, too, like something really embarrassing was about to happen.

"Say something!" Kitty Lamar whispered.

But Eddy Ray just kept staring at the Greaser, like he was seeing his past or himself or maybe our whole generation before we went to war.

The Greaser glanced sideways, scratched at a place under one eye, then started to sit down.

"These guys are not only great musicians," Eddy Ray began, "they're three of the best guys I ever knew. It's an honor to have them here tonight. It's an honor to be their friend. They make me proud to be an American."

I thought the yelling and table-pounding from the crowd was going to blow the glass out of the windows.

The rest of the night should have been wonderful. It wasn't. Not for me, at least. In my lifetime I guess I've known every kind of person there is—brig rats, pimps, drug pushers, disk jockeys on the take, promoters who split for Vegas with the cashbox, and, my favorite bunch, scrubbed-down ministers who preach Jesus on Sunday and Wednesday night and the rest of the week screw teenage girls in their congregations. But none of them can hold a candle to a friend who stabs you in the back. That kind of person not only steals your faith in your fellow human beings, he makes you resent yourself.

We had taken a break about 11:30 p.m., figuring to do one more set before we called it a night, and I hadn't seen the Greaser in the last hour or so. I glanced out the back window at a gazebo that was perched up on a little hill above a picnic area. I couldn't believe what I saw.

Silhouetted against the moon, the Greaser and Kitty Lamar were both standing inside the gazebo, the Greaser bending down toward her so their foreheads were almost touching, her ta-tas standing up inside her cowboy shirt like the upturned noses on a pair of puppy dogs. I felt sick inside. No, that doesn't describe it. I wanted to tear the Greaser apart and personally drive Kitty Lamar down to the bus depot and throw her and her puppy dogs on the first westbound headed for Big D and all points south.

But that would have been easy compared to what I knew I had to do. I'd kept my silence ever since we'd first met Kitty Lamar at the roadhouse in Vinton. Now I was the guy who'd have to drive the nail through Eddy Ray's heart. Or at least that was what I told myself.

I waited until he and I were alone, at breakfast, the next day, in a restaurant with big windows that looked out on the Mississippi River. Eddy Ray was fanging down a plate of fried eggs, ham, grits, and toast and jam, hammering ketchup all over it, his face rested and happy.

"I got to tell you something," I said.

"It's not necessary. Eat up."

"You don't even know what I was gonna say."

"You're worried about the Greaser. I had a talk with him last night. Kitty Lamar and him are just friends."

"Yeah?" I said.

"You got a hearing problem?"

I stared out the window at a tug pushing a long barge piled with shale. The barge had gotten loose and was scraping against the pilings of the bridge. The port side had tipped upward against a piling and gray mounds of shale were sliding through the starboard deck rail, sinking as rapidly as concrete in the current.

"I saw her about five years back in a Port Arthur cathouse," I said. Eddy Ray studied the barge out on the river, chewing his food, his hair freshly barbered, razor-edged on the neck. "What were you doing there?"

"I got a few character defects myself. Least I don't go around claiming to be something I'm not," I said.

"Kitty Lamar already told me about it. So quit fretting your mind and your bowels over other people's business. I swear, R.B., I think you own stock in an aspirin company."

"I've heard her talking to him on the phone, Eddy Ray. They're taking you over the hurdles. I saw them in the gazebo last night, too. They looked like Siamese twins joined at the forehead."

This time he couldn't slip the punch and I saw the light go out of his eyes. He cut a small piece of ham and put it in his mouth. "I guess that puts a different twist on it," he said.

I hated myself for what I had just done.

Could it get worse? When we got back to the motel, the desk clerk told Eddy Ray to call the long-distance operator.

"Nobody answered the phone in my room?" Eddy Ray said.

"No, sir," the clerk said.

Kitty Lamar was supposed to have met us in the diner but hadn't shown up. Evidently she hadn't hung around the room, either. Eddy Ray got the callback operator on the line and she connected him with our agent in Houston, a guy who for biblical example had probably modeled his life on Pontius Pilate's.

The agency had booked us in a half-dozen places in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana, but as of that morning all our dates were canceled.

"What gives, Leon?" Eddy Ray said into the receiver. He was standing by the bed, puffing on a Lucky Strike while he listened, his back curved like a question mark. "Investigation? Into what? Listen to me, Leon, we didn't see anything, we don't know anything, we didn't do anything. I've got a total of thirty-seven dollars and forty cents to get us back to Houston. The air is showing through my tires. Are you listen—"

The line went dead. Eddy Ray removed the receiver from his ear, stared at it, and replaced it in the telephone cradle. "Do you have to be bald-headed to get a Fuller Brush route?" he said.

"Leon sold us out for another band?" I said.

"He says some Houston cops want to question us about Johnny's death."

"Why us?"

"They wonder if we saw a certain guy in Johnny's dressing room." Then Eddy Ray mentioned the name of a notorious promoter in the music business, a Mobbed-up guy who operated on both sides of the color line and scared both black and white people cross-eyed.

I felt my mouth go dry, my stomach constrict, the kind of feeling I used to get when I'd hear the first sounds of small-arms fire, like strings of Chinese firecrackers popping. "We'll go to California. You know what they say, 'Nobody dies in Santa Barbara.' How far is Needles from Santa Barbara?"

But it wasn't funny. We'd had it and we both knew it.