The Butterfly Lion - written by Michael Morpurgo

narrated by Virginia McKenna and Michael Morpurgo

illustrated by Christian Birmingham

Chilblains and Semolina Pudding

Butterflies live only short lives. They flower and flutter for just a few glorious weeks, and then they die. To see them, you have to be in the right place at the right time. And that’s how it was when I saw the butterfly lion – I happened to be in just the right place, at just the right time. I didn’t dream him. I didn’t dream any of it. I saw him, blue and shimmering in the sun, one afternoon in June when I was young. A long time ago. But I don’t forget. I mustn’t forget. I promised them I wouldn’t.

I was ten, and away at boarding school in deepest Wiltshire. I was far from home and I didn’t want to be. It was a diet of Latin and stew and rugby and detentions and cross-country runs and chilblains and marks and squeaky beds and semolina pudding. And then there was Basher Beaumont who terrorised and tormented me, so that I lived every waking moment of my life in dread of him. I had often thought of running away, but only once ever plucked up the courage to do it.

I was homesick after a letter from my mother. Basher Beaumont had cornered me in the bootroom and smeared black shoe-polish in my hair. I had done badly in a spelling test, and Mr Carter had stood me in the corner with a book on my head all through the lesson – his favourite torture. I was more miserable than I had ever been before. I picked at the plaster in the wall, and determined there and then that I would run away.

I took off the next Sunday afternoon. With any luck I wouldn’t be missed till supper, and by that time I’d be home, home and free. I climbed the fence at the bottom of the school park, behind the trees where I couldn’t be seen. Then I ran for it. I ran as if bloodhounds were after me, not stopping till I was through Innocents Breach and out onto the road beyond. I had my escape all planned. I would walk to the station – it was only five miles or so – and catch the train to London. Then I’d take the underground home. I’d just walk in and tell them that I was never, ever going back.

There wasn’t much traffic, but all the same I turned up the collar of my raincoat so that no one could catch a glimpse of my uniform. It was beginning to rain now, those heavy hard drops that mean there’s more of the same on the way. I crossed the road, and ran along the wide grass verge under the shelter of the trees.

Beyond the grass verge was a high brick wall, much of it covered in ivy. It stretched away into the distance, continuous as far as the eye could see, except for a massive arched gateway at the bend of the road. A great stone lion bestrode the gateway. As I came closer I could see he was roaring in the rain, his lip curled, his teeth bared. I stopped and stared up at him for a moment. That was when I heard a car slowing down behind me. I did not think twice. I pushed open the iron gate, darted through, and flattened myself behind the stone pillar. I watched the car until it disappeared round the bend.

To be caught would mean a caning, four strokes, maybe six, across the back of the knees. Worse, I would be back at school, back to detentions, back to Basher Beaumont. To go along the road was dangerous, too dangerous. I would try to cut across country to the station. It would be longer that way, but far safer.

Strange Meeting

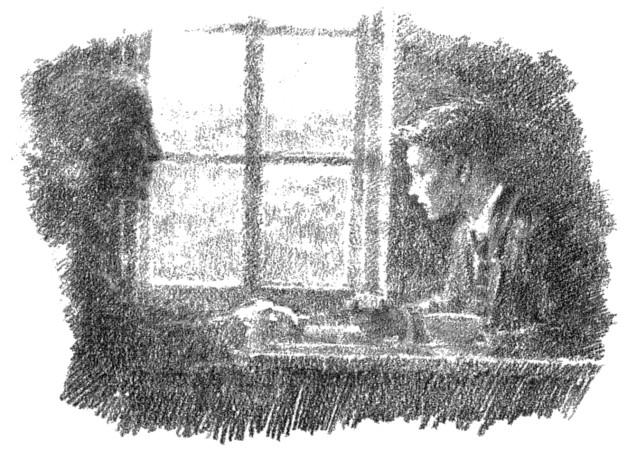

I was still deciding which direction to take when I heard a voice from behind me.

“Who are you? What do you want?”

I turned.

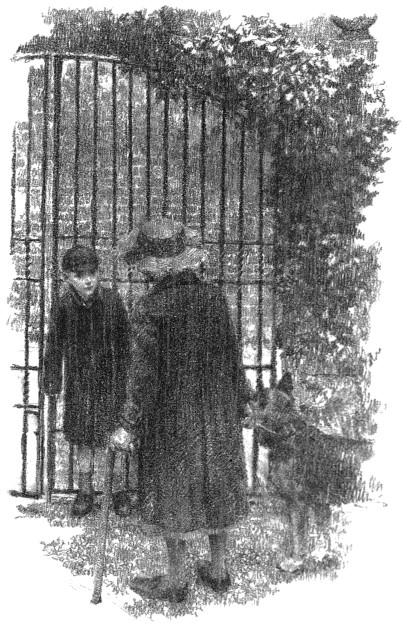

“Who are you?” she asked again. The old lady who stood before me was no bigger than I was. She scrutinised me from under the shadow of her dripping straw hat. She had piercing dark eyes that I did not want to look into.

“I didn’t think it would rain,” she said, her voice gentler. “Lost, are you?”

I said nothing. She had a dog on a leash at her side, a big dog. There was an ominous growl in his throat, and his hackles were up all along his back.

She smiled. “The dog says you’re on private property,” she went on, pointing her stick at me accusingly. She edged aside my raincoat with the end of her stick. “Run away from that school, did you? Well, if it’s anything like it used to be, I can’t say I blame you. But we can’t just stand here in the rain, can we? You’d better come inside. We’ll give him some tea, shall we, Jack? Don’t you worry about Jack. He’s all bark and no bite.” Looking at Jack, I found that hard to believe.

I don’t know why, but I never for one moment thought of running off. I often wondered later why I went with her so readily. I think it was because she expected me to, willed me to somehow. I followed the old lady and her dog up to the house, which was huge, as huge as my school. It looked as if it had grown out of the ground. There was hardly a brick or a stone or a tile to be seen. The entire building was smothered in red creeper, and there were a dozen ivy-clad chimneys sprouting skywards from the roof.

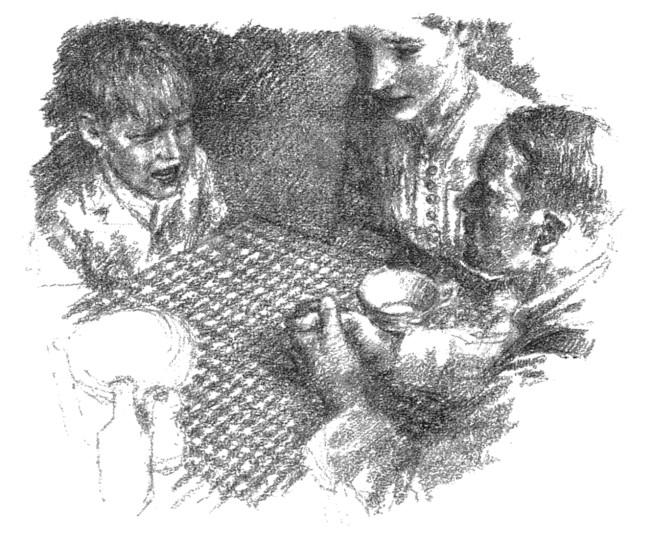

We sat down close to the stove in a vast vaulted kitchen. “The kitchen’s always the warmest place,” she said, opening the oven door. “We’ll have you dry in no time. Scones?” she went on, bending down with some difficulty and reaching inside. “I always have scones on a Sunday. And tea to wash it down. All right for you?” She went on chatting away as she busied herself with the kettle and the teapot. The dog eyed me all the while from his basket, unblinking. “I was just thinking,” she said. “You’ll be the first young man I’ve had inside this house since Bertie.” She was silent for a while.

The smell of the scones wafted through the kitchen.

I ate three before I even touched my tea. They were sweet and crumbly, and succulent with melting butter. She talked on merrily again, to me, to the dog – I wasn’t sure which. I wasn’t really listening. I was looking out of the window behind her. The sun was bursting through the clouds and lighting the hillside. A perfect rainbow arched through the sky. But miraculous though it was, it wasn’t the rainbow that fascinated me. Somehow, the clouds were casting a strange shadow over the hillside, a shadow the shape of a lion, roaring like the one over the archway

“Sun’s come out,” said the old lady, offering me another scone. I took it eagerly. “Always does, you know. It may be difficult to remember sometimes, but there’s always sun behind the clouds, and the clouds do go in the end. Honestly.”

She watched me eat, a smile on her face that warmed me to the bone.

“Don’t think I want you to go, because I don’t. Nice to see a boy eat so well, nice to have the company; but all the same, I’d better get you back to school after you’ve had your tea, hadn’t I? You’ll only be in trouble otherwise. Mustn’t run off, you know. You’ve got to stick it out, see things through, do what’s got to be done, no matter what.” She was looking out of the window as she spoke. “My Bertie taught me that, bless him, or maybe I taught him. I can’t remember now.” And she went on talking and talking, but my mind was elsewhere again.

The lion on the hillside was still there, but now he was blue and shimmering in the sunlight. It was as if he were breathing, as if he were alive. It wasn’t a shadow any more. No shadow is blue. “No, you’re not seeing things,” the old lady whispered. “It’s not magic. He’s real enough. He’s our lion, Bertie’s and mine. He’s our butterfly lion.”

“What d’you mean?” I asked.

She looked at me long and hard. “I’ll tell you if you like,” she said. “Would you like to know? Would you really like to know?”

I nodded.

“Have another scone first and another cup of tea. Then I’ll take you to Africa where our lion came from, where my Bertie came from too. Bit of a story, I can tell you. You ever been to Africa?”

“No,” I replied.

“Well, you’re going,” she said. “We’re both going.”

Suddenly I wasn’t hungry any more. All I wanted now was to hear her story. She sat back in her chair, gazing out of the window. She told it slowly, thinking before each sentence; and all the while she never took her eyes off the butterfly lion. And neither did I.

Timbavati

Bertie was born in South Africa, in a remote farmhouse near a place called Timbavati. It was shortly after Bertie first started to walk that his mother and father decided a fence must be put around the farmhouse to make a compound where Bertie could play in safety It wouldn’t keep the snakes out – nothing could do that – but at least Bertie would be safe now from the leopards, and the lions and the spotted hyenas. Enclosed within the compound were the lawn and gardens at the front of the house, and the stables and barns at the back – all the room a child would need or want, you might think. But not Bertie.

The farm stretched as far as the eye could see in all directions, twenty thousand acres of veld. Bertie’s father farmed cattle, but times were hard. The rains had failed too often, and many of the rivers and waterholes had all but dried up. With fewer wildebeest and impala to prey on, the lions and leopards would sneak up on the cattle whenever they could. So Bertie’s father was more often than not away from home with his men, guarding the cattle. Every time he left, he’d say the same thing: “Don’t you ever open that gate, Bertie, you hear me? There’s lions out there, leopards, elephants, hyenas. You stay put, you hear?” Bertie would stand at the fence and watch him ride out, and he would be left behind with his mother, who was also his teacher. There were no schools for a hundred miles. And his mother too was always warning him to stay inside the fence. “Look what happened in Peter and the Wolf,” she would say.

His mother was often sick with malaria, and even when she wasn’t sick she would be listless and sad. There were good days, days when she would play the piano for him and play hide-and-seek around the compound. Or he’d sit on her lap on the sofa out on the veranda and she’d just talk and talk, all about her home in England, about how much she hated the wildness and the loneliness of Africa, and about how Bertie was everything to her. But they were rare days. Every morning he’d climb into her bed and snuggle up to her, hoping against hope that today she’d be well and happy; but so often she wasn’t, and Bertie would be left on his own again, to his own devices.

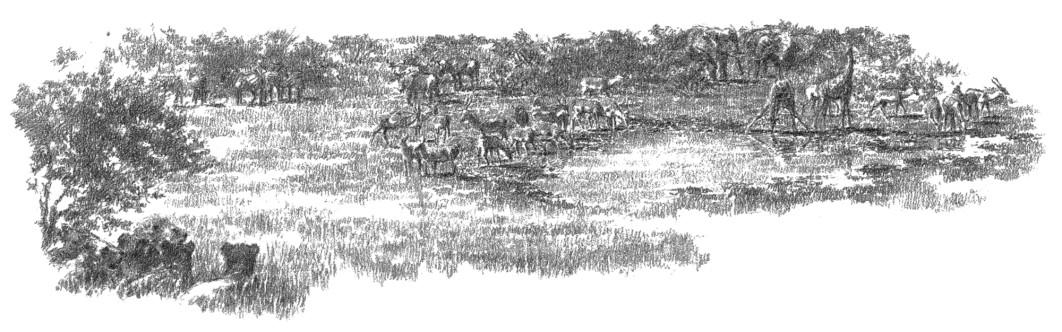

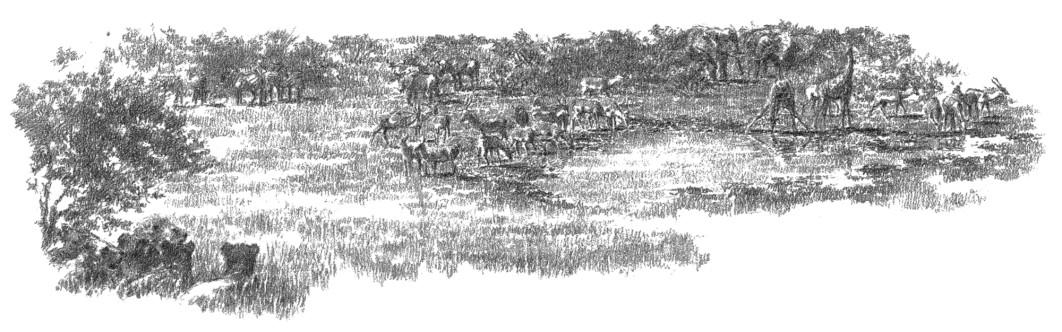

There was a waterhole downhill from the farmhouse, and some distance away. That waterhole, when there was water in it, became Bertie’s whole world. He would spend hours in the dusty compound, his hands gripping the fence, looking out at the wonders of the veld, at the giraffes drinking, spread-legged, at the waterhole; at the browsing impala, tails twitching, alert; at the warthogs snorting and snuffling under the shade of the shingayi trees; at the baboons, the zebras, the wildebeests, and the elephants bathing in the mud. But the moment Bertie always longed for was when a pride of lions came padding out of the veld. The impala were the first to spring away, then the zebra would panic and gallop off. Within seconds the lions would have the waterhole to themselves, and they would crouch to drink.

From the safe haven of the compound Bertie looked and learned as he grew up. By now, he could climb the tree by the farmhouse, and sit high in its branches. He could see better from up there. He would wait for his lions for hours on end. He got to know the life of the waterhole so well that he could feel the lions were out there, even before he saw them.

Bertie had no friends to play with, but he always said he was never lonely as a child. At night he loved reading his books and losing himself in the stories, and by day his heart was out in the veld with the animals. That was where he yearned to be. Whenever his mother was well enough, he would beg her to take him outside the compound, but her answer was always the same.

“I can’t, Bertie. Your father has forbidden it,” she’d say. And that was that.

The men would come home with their stories of the veld, of the family of cheetahs sitting like sentinels on their kopje, of the leopard they had spotted high in his tree larder watching over his kill, of the hyenas they had driven off, of the herd of elephants which had stampeded the cattle. And Bertie would listen wide-eyed, agog. Again and again he asked his father if he could go with him to help guard the cattle. His father just laughed, patted his head, and said it was man’s work. He did teach Bertie how to ride, and how to shoot too, but always within the confines of the compound.

Week in, week out, Bertie had to stay behind his fence. He made up his mind though, that if no one would take him out into the veld, then one day he would go by himself. But something always held him back. Perhaps it was one of those tales he’d been told of black mamba snakes whose bite would kill you within ten minutes, of hyenas whose jaws would crunch you to bits, of vultures who would finish off anything that was left so that no one would ever find even the bits. For the time being he stayed behind the fence. But the more he grew up, the more his compound became a prison to him.

One evening – Bertie must have been about six years old by now – he was sitting high up in the branches of his tree, hoping against hope the lions might come down for their sunset drink as they often did. He was thinking of giving up, for it would soon be too dark to see much now, when he saw a solitary lioness come down to the waterhole. Then he saw that she was not alone. Behind her, and on unsteady legs, came what looked like a lion cub – but it was white, glowing white in the gathering gloom of dusk.

While the lioness drank, the cub played at catching her tail; and then, when she had had her fill, the two of them slipped away into the long grass and were gone.

Bertie ran inside, screaming with excitement. He had to tell someone, anyone. He found his father working at his desk.

“Impossible,” said his father. “You’re seeing things that aren’t there, or you’re telling fibs – one of the two.”

“I saw him. I promise,” Bertie insisted. But his father would have none of it, and sent him to his room for arguing.

His mother came to see him later. “Anyone can make a mistake, Bertie dear,” she said. “It must have been the sunset. It plays tricks with your eyes sometimes. There’s no such thing as a white lion.”

The next evening Bertie watched again at the fence, but the white lion cub and the lioness did not come, nor did they the next evening, nor the next. Bertie began to think he must have been dreaming it.

A week or more passed, and there had been only a few zebras and wildebeest down at the waterhole. Bertie was already upstairs in his bed when he heard his father riding into the compound, and then the stamp of his heavy boots on the veranda.

“We got her! We got her!” he was saying. “Huge lioness, massive she was. She’s taken half a dozen of my best cattle in the last two weeks. Well, she won’t be taking any more.”

Bertie’s heart stopped. In that one terrible moment he knew which lioness his father was talking about. There could be no doubt about it. His white lion cub had been orphaned.

“But what if,” Bertie’s mother was saying, “what if she had young ones to feed? Perhaps they were starving.”

“So would we be if we let it go on. We had to shoot her,” his father retorted.

Bertie lay there all night listening to the plaintive roaring echoing through the veld, as if every lion in Africa was sounding a lament. He turned his face into his pillow and could think of nothing but the orphaned white cub, and he promised himself there and then that if ever the cub came down to the waterhole looking for his dead mother, then he would do what he had never dared to do, he would open the gate and go out and bring him home. He would not let him die out there all alone. But no lion cub came to his waterhole. All day, every day, he waited for him to come, but he never came.

Bertie and the Lion

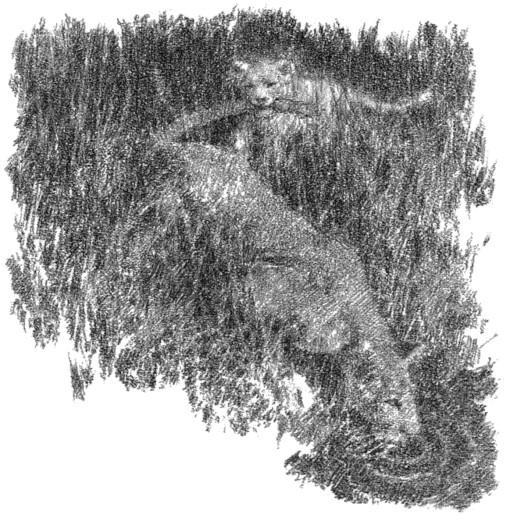

One morning, a week or so later, Bertie was woken by a chorus of urgent neighing. He jumped out of his bed and ran to the window. A herd of zebras was scattering away from the waterhole, chased by a couple of hyenas. Then he saw more hyenas, three of them, standing stock still, noses pointing, eyes fixed on the waterhole. It was only now that Bertie saw the lion cub. But this one wasn’t white at all. He was covered in mud, with his back to the waterhole, and he was waving a pathetic paw at the hyenas who were beginning to circle. The lion cub had nowhere to run to, and the hyenas were sidling ever closer.

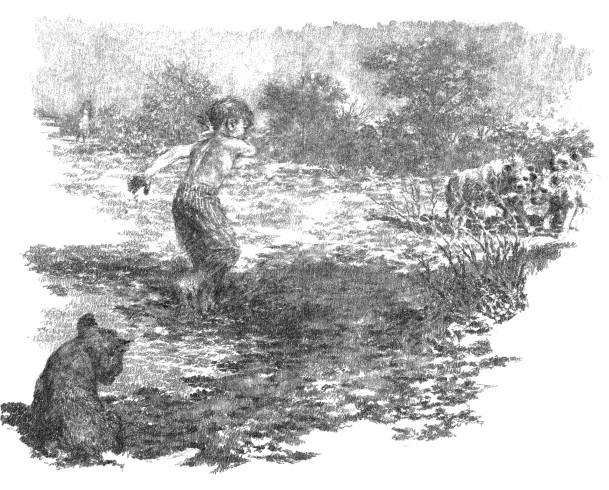

Bertie was downstairs in a flash, leaping off the veranda and racing barefoot across the compound, shouting at the top of his voice. He threw open the gate and charged down the hill towards the waterhole, yelling and screaming and waving his arms like a wild thing. Startled at this sudden intrusion, the hyenas turned tail and ran, but not far. Once within range Bertie hurled a broadside of pebbles at them, and they ran off again, but again not far. Then he was at the waterhole and between the lion cub and the hyenas, shouting at them to go away. They didn’t. They stood and watched, uncertain for a while. Then they began to circle again, closer, closer…

That was when the shot rang out. The hyenas bolted into the long grass, and were gone. When Bertie turned round he saw his mother in her nightgown, rifle in hand, running towards him down the hill. He had never seen her run before. Between them they gathered up the mud-matted cub and brought him home. He was too weak to struggle, though he tried. As soon as they had given him some warm milk, they dunked him in the bath to wash him. As the first of the mud came off, Bertie saw he was white underneath.

“You see!” he cried triumphantly. “He is white! He is. I told you, didn’t I? He’s my white lion!” His mother still could not bring herself to believe it. Five baths later, she had to.

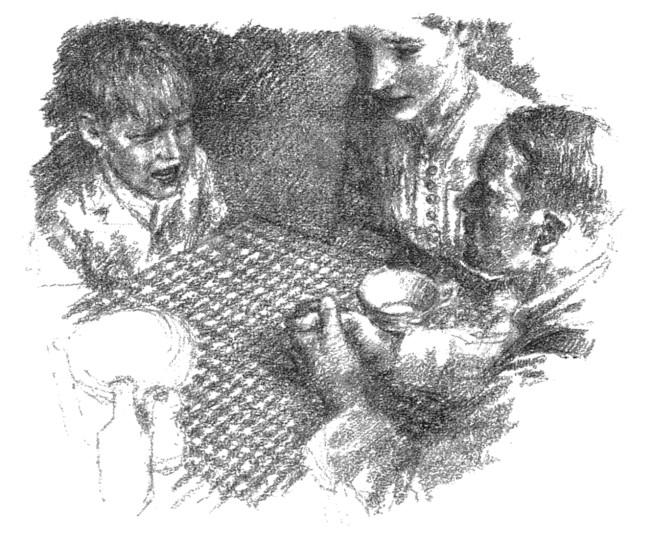

They sat him down by the stove in a washing basket and fed him again, all the milk he could drink, and he drank the lot. Then he lay down and slept.

He was still asleep when Bertie’s father got back at lunch time. They told him how it had all happened.

“Please, Father. I want to keep him,” Bertie said.

“And so do I,” said his mother. “We both do.” And she spoke as Bertie had never heard her speak before, her voice strong, determined.

Bertie’s father didn’t seem to know quite how to reply. He just said: “We’ll talk about it later,” and then he walked out.

They did talk about it later when Bertie was supposed to be in bed. He wasn’t, though. He heard them arguing. He was outside the sitting-room door, watching, listening. His father was pacing up and down.

“He’ll grow up, you know,” he was saying. “You can’t keep a grown lion, you know that.”

“And you know we can’t just throw him to the hyenas,” replied his mother. “He needs us, and maybe we need him. He’ll be someone for Bertie to play with for a while.” And then she added sadly: “After all, it’s not as if he’s going to have any brothers and sisters, is it?”

At this, Bertie’s father went over to her and kissed her gently on the forehead. It was the only time Bertie had ever seen him kiss her.

“All right then,” he said. “All right. You can keep your lion.”

So the white lion cub came to live amongst them in the farmhouse. He slept at the end of Bertie’s bed. Wherever Bertie went, the lion cub went too – even to the bathroom, where he would watch Bertie have his bath and lick his legs dry afterwards. They were never apart. It was Bertie who saw to the feeding – milk four times a day from one of his father’s beer bottles – until later on when the lion cub lapped from a soup bowl. There was impala meat whenever he wanted it, and as he grew – and he grew fast – he wanted more and more of it.

For the first time in his life Bertie was totally happy. The lion cub was all the brothers and sisters he could ever want, all the friends he could ever need. The two of them would sit side by side on the sofa out on the veranda and watch the great red sun go down over Africa, and Bertie would read him Peter and the Wolf, and at the end he would always promise him that he would never let him go off to a zoo and live behind bars like the wolf in the story And the lion cub would look up at Bertie with his trusting amber eyes.

“Why don’t you give him a name?” his mother asked one day.

“Because he doesn’t need one,” replied Bertie. “He’s a lion, not a person. Lions don’t need names.”

Bertie’s mother was always wonderfully patient with the lion, no matter how much mess he made, how many cushions he pounced on and ripped apart, no matter how much crockery he smashed. None of it seemed to upset her. And strangely, she was hardly ever ill these days. There was a spring to her step, and her laughter pealed around the house. His father was less happy about it. “Lions,” he’d mutter on, “should not live in houses. You should keep him outside in the compound.” But they never did. For both mother and son, the lion had brought new life to their days, life and laughter.

Running Free

It was the best year of Bertie’s young life. But when it ended, it ended more painfully than he could ever have imagined. He’d always known that one day when he was older he would have to go away to school, but he had thought and hoped it would not be for a long time yet. He’d simply put it out of his mind.

His father had just returned home from Johannesburg after his yearly business trip. He broke the news at supper that first evening. Bertie knew there was something in the wind. His mother had been sad again in recent days, not sick, just strangely sad. She wouldn’t look him in the eye and she winced whenever she tried to smile at him. The lion had just lain down beside him, his head warm on Bertie’s feet, when his father cleared his throat and began. It was going to be a lecture. Bertie had had them before often enough, about manners, about being truthful, about the dangers of leaving the compound.

“You’ll soon be eight, Bertie,” he said. “And your mother and I have been doing some thinking. A boy needs a proper education, a good school. Well, we’ve found just the right place for you, a school near Salisbury in England. Your Uncle George and Aunt Melanie live nearby and have promised to look after you in the holidays, and to visit you from time to time. They’ll be father and mother to you for a while. You’ll get on with them well enough, I’m sure you will. They are fine, good people. So you’ll be off on the ship to England in July. Your mother will accompany you. She will spend the summer with you in Salisbury and after she has taken you to your school in September, she’ll then return here to the farm. It’s all arranged.”

As his heart filled with a terrible dread, all Bertie could think of was his white lion. “But the lion,” he cried, “what about the lion?”

“I’m afraid there’s something else I have to tell you,” his father said. Looking across at Bertie’s mother, he took a deep breath. And then he told him. He told him he had met a man whilst he was in Johannesburg, a Frenchman, a circus owner from France. He was over in Africa looking for lions and elephants to buy for his circus. He liked them young, very young, a year or less, so that he could train them up without too much trouble. Besides, they were easier and cheaper to transport when they were young. He would be coming out to the farm in a few days’ time to see the white lion for himself. If he liked what he saw, he would pay good money and take him away

It was the only time in his life Bertie had ever shouted at his father. “No! No, you can’t!”

It was rage that wrung the hot tears from him, but they soon gave way to silent tears of sadness and loss. There was no comforting him, but his mother tried all the same.

“We can’t keep him here for ever, Bertie,” she said. “We always knew that, didn’t we? And you’ve seen how he stands by the fence gazing out into the veld. You’ve seen him pacing up and down. But we can’t just let him out. He’d be all on his own, no mother to protect him. He couldn’t cope. He’d be dead in weeks. You know he would.”

“But you can’t send him to a circus! You can’t!” said Bertie. “He’ll be shut up behind bars. I promised him he never would be. And they’ll point at him. They’ll laugh at him. He’d rather die. Any animal would.” But he knew as he looked across the table at them that it was hopeless, that their minds were quite made up.

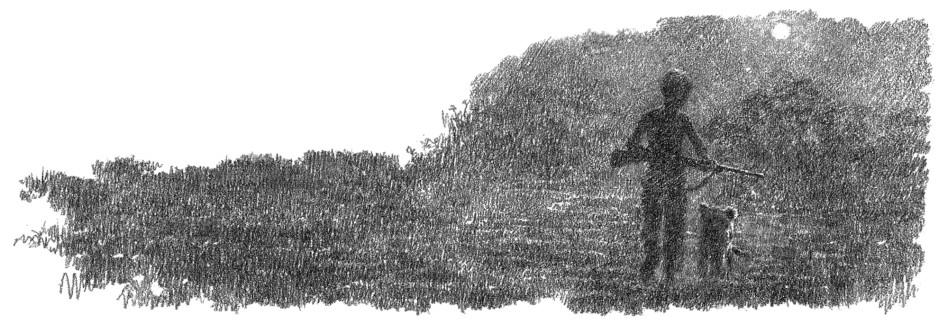

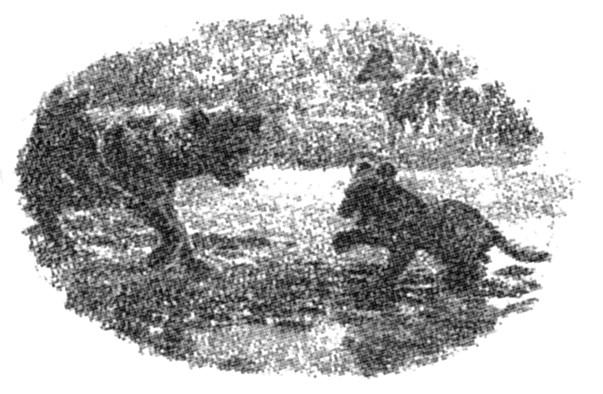

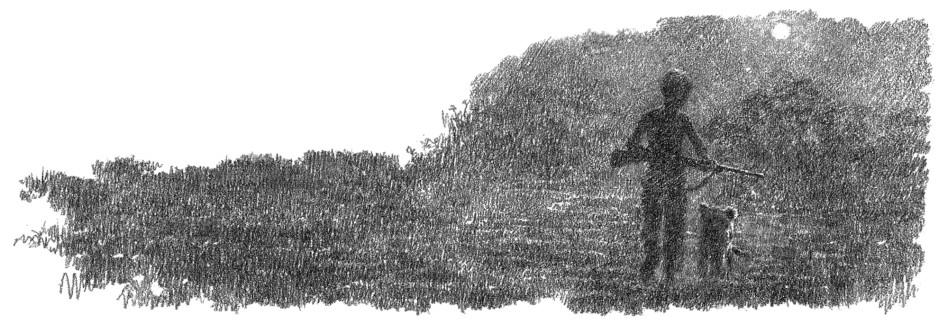

For Bertie the betrayal was total. That night he made up his mind what had to be done. He waited until he heard his father’s deep breathing next door. Then, with his white lion at his heels, he crept downstairs in his pyjamas, took down his father’s rifle from the rack and stepped out into the night. The compound gate yawned open noisily when he pushed it, but then they were out, out and running free. Bertie had no thought of the dangers around him, only that he must get as far from home as he could before he did it.

The lion padded along beside him, stopping every now and again to sniff the air. A clump of trees became a herd of elephants wandering towards them out of the dawn. Bertie ran for it. He knew how elephants hated lions. He ran and ran till his legs could run no more. As the sun came up over the veld he climbed to the top of a kopje and sat down, his arm round the lion’s neck. The time had come.

“Be wild now,” he whispered. “You’ve got to be wild. Don’t come home. Don’t ever come home. They’ll put you behind bars. You hear what I’m saying? All my life I’ll think of you, I promise I will. I won’t ever forget you.” And he buried his head in the lion’s neck and heard the greeting groan from deep inside him. He stood up. “I’m going now,” he said. “Don’t follow me. Please don’t follow me.” And Bertie clambered down off the kopje and walked away.

When he looked back, the lion was still sitting there watching him; but then he stood up, yawned, stretched, licked his lips and sprang down after him. Bertie shouted at him, but he kept coming. He threw sticks. He threw stones. Nothing worked. The lion would stop, but then as soon as Bertie walked on, he simply followed at a safe distance.

“Go back!” Bertie yelled, “you stupid, stupid lion! I hate you! I hate you! Go back!” But the lion kept loping after him whatever he did, whatever he said.

There was only one thing for it. He didn’t want to do it, but he had to. With tears filling his eyes and his mouth, he lifted the rifle to his shoulder and fired over the lion’s head. At once the lion turned tail and scampered away through the veld. Bertie fired again. He watched till he could see him no more, and then turned for home. He knew he’d have to face what was coming to him. Maybe his father would strap him – he’d threatened it often enough – but Bertie didn’t mind. His lion would have his chance for freedom, maybe not much of one. Anything was better than the bars and whips of a circus.