VIII. A SUCCESSFUL INTERROGATION

One hour later, in the dead of night, two men and a child presented themselves at no. 62, petite rue Picpus. The elder of the men lifted the door-knocker and knocked. This was Fauchelevent, Jean Valjean, and Cosette.

The two old men had gone and gotten Cosette from the fruit-hawker in the rue du Chemin-Vert, where Fauchelevent had dropped her off the night before. Cosette had spent the last twenty-four hours not knowing what to think and trembling silently. She trembled all the more as she had not wept. She hadn’t eaten either, or slept. The worthy fruit-hawker had put a hundred questions to her without getting more for an answer than the same mournful glance. Cosette did not let on for a second anything of all she had heard and seen over the last two days. She gathered that they were going through a crisis. She felt to her marrow that she had “to be good.” Who has not experienced the ultimate power of these three words delivered in a certain tone in the ear of a frightened child: “Not a word!” Fear is mute. Besides, no one can keep a secret the way a child can.

Only when, after this grim twenty-four hours, she clapped eyes on Jean Valjean again, did she let out a yelp of joy in which any thoughtful soul who had overheard her would have picked up the sense of an escape from a bottomless chasm.

Fauchelevent was from the convent and he knew the passwords. Every door opened. And thus the terrifying twin problem was solved: how to get out, how to get in.

The porter, who had his instructions, opened the little door of the tradesman’s entrance that was connected to the garden courtyard and that you could still see from the street twenty years ago, standing opposite the porte cochère. The porter let all three of them in through this door, and from there they reached the inner private visitors’ room where Fauchelevent had received the prioress’s orders the night before.

The prioress was waiting for them, rosary beads in hand. One of the vocal mothers was standing by her side with her veil down. A discreet candle lit up, we might almost say pretended to light up, the visitors’ room.

The prioress gave Jean Valjean the once-over. No eye can scrutinize as thoroughly as a downcast eye. Then she questioned him: “You are the brother?”

“Yes, Reverend Mother,” replied Fauchelevent.

“What is your name?”

Fauchelevent answered: “Ultime Fauchelevent.”

He had, in fact, had a brother named Ultime who was dead.

“What part of the country are you from?”

Fauchelevent answered: “From Picquigny, near Amiens.”

“How old are you?”

Fauchelevent answered: “Fifty.”

“What is your profession?”

Fauchelevent answered: “Gardener.”

“Are you a good Christian?”

Fauchelevent answered: “Everyone in the family is.”

“Is this little girl yours?”

Fauchelevent answered: “Yes, Reverend Mother.”

“You are her father?”

Fauchelevent answered: “Her grandfather.”

The vocal mother whispered to the prioress: “He answers well.”

Jean Valjean had not uttered a word. The prioress examined Cosette closely and whispered to the vocal mother: “She will be ugly.”

The two mothers chatted for a few minutes in voices barely above a whisper in a corner of the visitors’ room, then the prioress turned back and said: “Father Fauvent, you will have another knee pad and bell. We need two now.”

The next day, in fact, two little bells could be heard in the garden, and the nuns could not resist lifting a corner of their veils. At the bottom, under the trees, two men could be seen digging side by side, Fauvent and another man. Obviously an enormous event. The silence was broken long enough to say: “That’s the assistant gardener.”

The vocal mothers added: “He’s one of father Fauvent’s brothers.”

Jean Valjean was in fact properly fitted out; he had the leather knee pad and the bell; he was now officially accepted. His name was Ultime Fauchelevent.

The strongest determining argument for admission had been the prioress’s observation about Cosette: “She will be ugly.” This prognostic declared, the prioress immediately took Cosette to her heart and gave her a place in the boarding school as a charity case.

The move was only strictly logical. A lot of good it has done not having any mirrors in a convent, when women are so conscious of their appearance. Now, girls who feel they are pretty do not readily become nuns; luckily vocations declare themselves in inverse proportion to beauty, so hopes are higher for the ugly than for the beautiful. Hence the keen preference for ugly ducklings.

The whole episode greatly enhanced Fauchelevent’s standing. He had had a triple success: with Jean Valjean, whom he had saved and sheltered; with Gribier, the gravedigger, who said to himself, “He saved me that fine”; with the convent, which, thanks to him, kept Mother Crucifixion’s coffin under the altar, thereby eluding Caesar and satisfying God. There was a coffin with a corpse in Petit-Picpus and a coffin without a corpse in Vaugirard Cemetery; no doubt public order was profoundly disturbed, but it did not know it. As for the convent, its gratitude to Fauchelevent was great. Fauchelevent became the best of its servants and the most treasured of gardeners. At the very next visit of the archbishop, the prioress told the story to His Grace, half by way of a confession, half by way of a boast. When he left the convent, the archbishop spoke of it, very quietly, with approval to Monsieur de Latil, confessor to Monsieur, brother to the king, and, subsequently, to the archbishop of Rheims and a cardinal. Admiration for Fauchelevent traveled far and wide, for it got as far as Rome. We have actually seen a note addressed by the then-reigning pope, Leo XII, to one of his relatives, a monsignor in the nuncio’s residence in Paris with the same name as himself, Della Genga; in it can be read these lines: “It appears that in a convent in Paris there is an excellent gardener who is a saintly man, known as Fauvent.” Not a whiff of this triumph reached Fauchelevent in his shed; he continued to graft cuttings, to weed, and to cover his melon beds, without being brought up to speed on his excellence and his saintliness. He had no more suspicion of his splendid reputation than has a steer from Durham or Surrey whose portrait is published in the Illustrated London News with this caption: “The steer that won first prize in the cattle show.”

IX. ENCLOSURE

At the convent Cosette continued to keep silent.

Cosette quite naturally thought she was Jean Valjean’s daughter. Besides, not knowing anything, she could not say anything and then, in any case, she would not have said anything. We have just noted that nothing teaches children silence like calamity. Cosette had been through so much that she was afraid of everything, even to open her mouth, even to breathe. A word had so often brought an avalanche down on top of her! She had only just begun to feel safe since she had been in Jean Valjean’s hands. She got used to the convent quite quickly. Only, she longed for Catherine, but did not dare say so. One time, though, she said to Jean Valjean: “Father, if I’d known, I’d have brought her along.”

In becoming a boarder at the convent, Cosette had to adopt the uniform worn by the students of the house. Jean Valjean obtained permission to keep the clothes she was stripped of. This was the same mourning outfit he had made her wear when she left the Thénardiers’ pothouse. It had not yet had much wear. Jean Valjean packed this outfit, plus her woolen stockings and her shoes, with ample camphor and all the aromatics convents abound in, in a little suitcase that he managed to procure himself. He put the suitcase on a chair by his bed and he carried the key to it on him always. “Father,” Cosette asked him one day, “what is that box over there, then, that smells so good?”

Father Fauchelevent, apart from the glory we have just recounted and of which he was completely ignorant, was rewarded for his good deed; first, he was glad he’d done it, it made him happy; and then, he had a lot less work to do now he was sharing the load. Last, he really loved tobacco, and he found Monsieur Madeleine’s presence made it possible for him to take three times as much tobacco as in the past and with infinitely more relish, since Monsieur Madeleine paid for it.

The nuns did not adopt the name of Ultime; they called Jean Valjean “the other Fauvent.”

If those holy old maids had had a fraction of Javert’s perceptiveness, they would have wound up noticing that, whenever there was some errand to run outside for the maintenance of the garden, it was always the elder Fauchelevent, the old one, the infirm one, the lame one, who went out, and never the other man; but, either because eyes forever fixed on God don’t know how to spy, or because they were, out of preference, busy watching each other, they noticed nothing.

And Jean Valjean did well to keep quiet and not to move. Javert watched the quartier for a good long month or more.

The convent was for Jean Valjean like an island surrounded by sheer cliffs. Those four walls were now the world for him. He saw enough of the sky from there to be serene and enough of Cosette to be happy.

A very sweet life began for him once more.

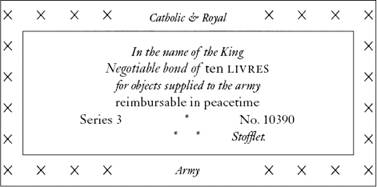

He lived with old Fauchelevent in the shed at the bottom of the garden. This shack, built out of rubble and still standing in 1845, consisted, as we have already said, of three rooms, all of which were completely bare. Father Fauchelevent had insisted Monsieur Madeleine have the main room, and he was forced to accept it, for Jean Valjean had resisted in vain. The walls of this room, apart from two nails for hanging up the knee pad and the basket, were adorned only with an example of the royalist paper money of ’93 stuck on the wall over the mantelpiece. Here is an exact replica:

This assignat from La Vendée had been nailed to the wall by the previous gardener, an old member of the Chouan party who had died in the convent and been replaced by Fauchelevent.

Jean Valjean worked all day in the garden and was extremely useful there. He had once been a pruner, after all, and was glad to find himself a gardener again. You will recall that he was full of all kinds of agricultural secrets and recipes for growing things. He put them to good use. Nearly all the trees in the orchard were wildings; he budded them and got them to yield excellent fruit.

Cosette had permission to go and spend an hour each day with him. As the sisters were sad and he was good, the child compared him with them and worshipped the ground he walked on. At the appointed hour she would run to the shed. When she entered this hovel, she filled it with paradise. Jean Valjean flourished and felt his happiness growing from the happiness he gave Cosette. The joy we inspire has this wonderful feature, which is that, far from dimming like any reflection, it comes back to us more radiant. At playtime, Jean Valjean would watch Cosette playing and running around from a distance and he could distinguish her laughter from the laughter of the other girls.

For Cosette now laughed.

Even the way Cosette looked had changed to a certain extent. All gloominess had vanished. Laughter is like sunshine; it chases winter away from the human face.

Cosette was still not pretty, but she had become charming regardless. She had a way of coming out with quite grown-up little notions in her sweet infantile voice.

When playtime was over and Cosette had gone back in, Jean Valjean would watch the windows of her classroom and at night he would get out of bed to watch the windows of the dormitory where she slept.

Besides, God has His ways; the convent, like Cosette, contributed to keeping up and completing the work of the bishop inside Jean Valjean. There is no doubt that one side of virtue leads to pride. There lies a bridge built by the devil. Jean Valjean had perhaps been, without knowing it, fairly close to both that side and that bridge, when Providence threw him into the Petit-Picpus convent. While he had compared himself only to the bishop, he had found himself unworthy and he had stayed humble; but for some little time he had been comparing himself to other men and pride had reared its ugly head. Who knows? He might well have ended up quietly returning to hate.

The convent stopped him on that slippery slope.

This was the second place of captivity he had seen. In his youth, in what had been for him the beginning of life, and then later, still only recently, he had seen another, an appalling and terrible place, whose austerities had always struck him as the iniquity of justice and the crime of the law. Today, after the galleys, he was seeing the cloister and thinking how he had been part of the prison system and was now a spectator, so to speak, of the cloister, and he compared them anxiously in his mind.

Sometimes he would lean on his spade and slowly descend the endless spirals of his thoughts.

He remembered his old companions and how miserable they were: they’d get up at the crack of dawn and work till nightfall; they were scarcely left enough time to shut their eyes; they slept on camp beds where mattresses no more than two thumbs thick were the only ones allowed in rooms that were only heated in the rawest months of the year; they were dressed in hideous red smocks; they were allowed, as a favor, to wear burlap pants in heatwaves and had a scrap of wool to slap on their backs in the coldest days of winter; they only drank wine and only ate meat when they were “on hard labor.” They lived without names, designated only by numbers and in some way reduced to mere figures, their eyes lowered, their voices lowered, their hair shorn, under the rod, in shame.

Then his mind reverted to the creatures he now had before his eyes.

These beings, too, lived with their hair shorn, their eyes lowered, their voices lowered, not in shame but in the full force of the world’s scorn, their backs not bruised by the rod but their shoulders lacerated by discipline. Their names had also vanished from among men and they only existed now under the most austere appellations. They never ate meat and never drank wine; they were dressed, not in red vests, but in black shrouds made of wool, heavy in summer, light in winter, without being able to take anything off or put anything on, without even being able to resort to cotton clothing or a woolen overcoat, according to the season; and for six months of the year they wore hair shirts that gave them fever. They lived not in rooms heated only in the worst days of winter, but in cells where fires were never lit; they slept not on mattresses only two inches thick but on straw. Last, they were not even allowed to sleep; every night, after a day of toil, as they sank with exhaustion into first sleep, the very moment when they were dozing off, scarcely warming up a little, they had to wake up, get up, and go and pray in the icy dark chapel, with both knees on the stone.

On certain days, every one of these beings took a turn putting in twelve hours at a stretch kneeling on the flagstones or prostrate face down on the ground, arms out on both sides like a cross.

The first lot were men; these were women.

What had these men done? They had stolen, raped, looted, killed, murdered. They were bandits, forgers, poisoners, arsonists, murderers, parricides. What had these women done? They had done nothing.

On one side, armed robbery, fraud, theft, violence, lechery, homicide, every known form of sacrilege, every variety of assault; on the other, one thing only: innocence. Perfect innocence, almost lifted aloft in some mysterious assumption, still tethered to the ground through virtue, already tethered to heaven through holiness.

On one side, the whispered mutual avowal of crimes; on the other, the confession of sins said out loud. And what crimes! And what sins!

On one side, primeval sludge; on the other, an ineffable perfume. On one side, a moral pestilence, kept in custody, penned in under cannon and slowly devouring the plague-addled victims; on the other, a chaste kindling of all souls at the same hearth. There, darkness; here, shadow, but shadow full of flashes of light, and flashes of light full of radiance.

Two places of slavery; but in the first, deliverance is possible, a legal limit is always in sight, and there’s always escape. In the second, perpetuity; the only hope, in the extremely distant future, that glimmer of freedom mankind calls death.

In the first, you were chained up in mere chains; in the other, you were chained by your faith.

What emerged from the first? Endless malediction, the gnashing of teeth, hate, a desperate depravity, a cry of rage against human association, utter contempt for heaven. What issued from the second? Benediction and love. And in these two places, so similar and yet so different, these two species of being, so very different, accomplished the same duty, atonement.

Jean Valjean understood perfectly well the atonement involved in the first, personal atonement, atonement for oneself. But he did not understand atonement for others, that suffered by these creatures, blameless and without stain, and he asked himself with a shudder: Atonement for what? What atonement?

A voice in his conscience answered him: the most divine form of human generosity, atonement for others.

Here we will refrain from adding our personal theories, we are merely the narrator, putting ourselves in Jean Valjean’s shoes, seeing with his eyes and translating his impressions.

He had before his very eyes the sublime summit of self-abnegation, the highest peak of virtue possible—that innocence that forgives men for their sins and atones in their stead; servitude endured, torture accepted, torment sought out by souls who have not sinned in order to exempt from such torment souls that have faltered; the love of humanity losing itself in the love of God, yet remaining there, distinct and imploring; gentle weak creatures taking on the misery of those who are punished and the smile of those who are rewarded. And he remembered that he had dared to feel sorry for himself!

Often in the middle of the night, he would get up to listen to the grateful chanting of these innocent creatures overwhelmed by austerities, and he felt the blood run cold in his veins to think that those who were justly punished did not raise their voices to the heavens except to blaspheme and that he, miserable bastard, had shaken his fist at God.

One thing was striking and gave him pause for profound thought, like a warning whispered by Providence itself: The walls scaled, fences hurdled, luck tried to the death, the long hard climb uphill, all these same efforts he had made to get out of the other place of atonement, he had made to get into this one here. Was this an emblem of his fate?

This house was a prison, too, and looked horribly like the other abode he had fled, and yet he had never imagined anything remotely like it.

He saw, once more, grates, bolts, iron bars—to guard whom? Angels. These high walls that he had seen around tigers, he saw them once more around sheep.

This was a place of atonement and not of punishment; and yet it was even more austere, more mournful, and more merciless than the other one. These virgins were more savagely beaten down than the convicts. A cold, harsh wind, the wind that had frozen his childhood, swept through that grated, padlocked pit of vultures; an even more bitter and painful blast blew in this cage of doves.

Why?

When he thought of these things, everything in him became deeply absorbed in this mystery of sublimeness. In these meditations, pride evaporated. He circled himself, over and over again; he felt himself to be puny and he wept many times. All that had entered his life in the last six months brought him back to the holy injunctions of the bishop—Cosette, through love, the convent, through humility.

Sometimes, in the evening, at dusk, at the hour when the garden was deserted, he could be seen on his knees in the middle of the path that ran alongside the chapel, in front of the window he had looked in the night he arrived, turned to face the place where he knew that the sister making atonement lay in prostration and in prayer. He prayed, kneeling like this before this sister. It seemed that he did not dare kneel directly before God.

All that surrounded him, the peaceful garden, the fragrant flowers, the children letting out joyful cries, these grave and simple women, the silent cloister, slowly penetrated him, and little by little his soul filled with silence like the cloister, with perfume like the flowers, with peace like the garden, with simplicity like the women, with joy like the children. And then he reflected that it was two houses of God that had taken him in, one after the other, at the two critical moments of his life, the first when all doors had shut in his face and human society had pushed him away, the second at the moment when human society had set off after him again and when jail was once more opening its doors; and that without the first, he would have lapsed into crime again, and without the second, into torment.

His whole heart melted in gratitude and he felt more and more love.

Several years went by this way; Cosette was growing up.